UCLA faculty voice: Keeping John Muir’s legacy alive in the 21st century

Today that means thriving urban wilderness areas and redefining conservation for California’s changing

Today that means thriving urban wilderness areas and redefining conservation for California’s changing

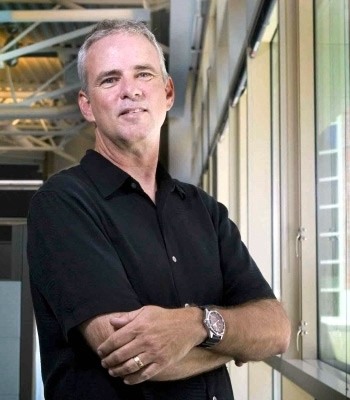

By Glen MacDonald

Originally posted in UCLA Newsroom

Glen MacDonald is the John Muir Memorial Chair and distinguished professor of geography at UCLA. He studies the causes and impacts of environmental change. This column appeared Dec. 24 on Zócalo Public Square, as part of Thinking L.A., Zócalo’s partnership with UCLA.

Glen MacDonald is the John Muir Memorial Chair and distinguished professor of geography at UCLA. He studies the causes and impacts of environmental change. This column appeared Dec. 24 on Zócalo Public Square, as part of Thinking L.A., Zócalo’s partnership with UCLA.

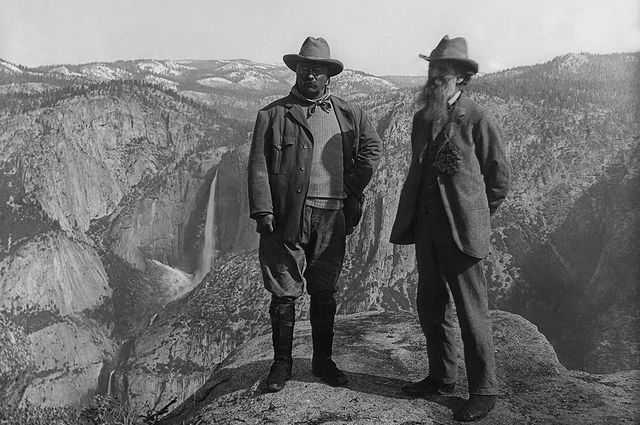

The pioneering environmentalist John Muir was no great fan of cities. In 1868, he hightailed it out of San Francisco as fast as he could for the Sierra Nevada. He later referred to Los Angeles as “that handsome conceited little town” and similarly skedaddled away pronto to the San Gabriel Mountains. Yet it was in Los Angeles, on Christmas Eve 100 years ago, that Muir took leave of this world. A century after Muir’s death, will the cities of California serve as the graveyard of his legacy or a place of rebirth?

Muir was focused on the preservation of nature. “In God’s wildness lies the hope of the world—the great fresh unblighted, unredeemed wilderness,” he wrote. To him, a place like Yosemite was the “people’s cathedral” and he had faith that if people experienced it, they would become converts to the cause of preserving wilderness. He felt that the National Park system was the only sure way to protect forever these sacred places. The 52 million acres of National Park land are his gift to us and hope for both our future and the wilderness he cherished.

I’ve roamed many of the lands Muir set aside for us and have also taught about the American environmental movement and John Muir for a number of years. And I know that 21st-century America presents deep challenges to Muir’s legacy. In 1914, federal debt stood at 4 percent of gross domestic product. Today it is an astounding 70 percent. The capacity of the federal government to acquire and manage wilderness lands is diminishing and there seems little chance of a reversal. Since 2000, the portion of the federal budget allocated to the National Park Service declined by about 40 percent relative to other programs.

Muir preached to an overwhelmingly white elite that had the means to disengage from the cities when they desired, who worked the levers of power to save his beloved wild lands. Today, 95 percent of Californians now live in urban areas and whites have made up a minority of our state’s population since 1999. The numbers of visitors to our National Parks who are African-American or Latino are far underrepresented relative to their proportion of the U.S. population today. And some projections suggest that visitor numbers in general will decline despite a rise in total population over the next century. Membership in environmental advocacy groups such as the Sierra Club (which was founded by Muir) and the Nature Conservancy—which some hope can rescue park lands—is overwhelmingly white and aging. In the case of the Nature Conservancy, the current average age of new members is 62. The constituency for conservation as we have known it is melting away.

If we want to preserve America’s appreciation of nature and support for wilderness preservation, we must focus on cities and those who live in them. What easier way is there to expose people to nature than right in their own backyards? As a boy, my parents took me to Yosemite and it made an impression, but I spent more time at home in San Jose playing along the banks of Penitencia Creek in Alum Rock Park and Coyote Creek in Kelley Park. All of this led to a love of nature and a life devoted to working on the environment.

If they work together, it can actually be affordable for cash-strapped agencies to set aside new land for conservation that’s accessible for an urban population. Take, as an example, the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. Through a joint partnership of federal, state, and local government and private parties, 450,000 acres have been put aside for conservation and recreational uses. This has been done incrementally over a 36-year period and costs are shared between the partners. Thanks to these efforts, mountain lions are again roaming the hills above Hollywood.

Millions of visitors also have easy access to diverse communities of plants, birds, mammals, and fish at places like San Bruno Mountain State Park in the midst of the San Francisco Peninsula, and the Guadalupe River Park Conservancy and Coyote Creek Trail that run through the very heart of Silicon Valley in San Jose. San Bruno Mountain is a refuge for endangered butterflies such as the San Bruno Elfin, Mission Blue, Callippe Silverspot, and Bay Checkerspot, while Chinook salmon migrate up the Guadalupe River and other charismatic species such as the California beaver, wild turkey, and grey fox have been newly sighted roaming San Jose’s riverside parks.

If you build it, will they always come? In 2013, the Santa Monica National Recreation Area had 633,000 visitors and San Bruno Mountain had just over 55,000. A good start, but these are urban areas with a combined total population of more than 20 million people. Clearly more needs to be done to engage people with the natural world they are part of — even in the midst of the city. Several organizations are leading the way, such as Outdoor Afro with its local nature hikes to the redwood groves above Oakland and the Santa Monica Mountains or the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles with its new three and a half acres of Nature Garden in the heart of L.A. and emphasis on developing young citizen scientists to study urban nature. Even Muir’s venerable Sierra Club has joined the effort with its Inner City Outings program.

By expanding on Muir’s vision to value and explore the nature that is right here in our cities, we just might be able to build a new constituency and preserve his legacy. In the 21st century the fate of nature in California is more likely to be determined by the young Hispanic girl who becomes fascinated by a butterfly in a reclaimed brownfield than by John Muir and the distant peaks of Yosemite.