Connecting Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: What’s the Evidence?

We believe that healthy natural ecosystems are crucial for the well-being of human communities, too. But what’s the evidence?

It’s mixed — strong for economic health, but less so for human health and other well-being measures, according to a report just out in the journal Nature from a team of researchers including Samantha Cheng, who recently completed her PhD in ecology and evolutionary biology at UCLA.

In the new year, Cheng begins a postdoctoral fellowship with a multidisciplinary research team in an exciting program called SNaP—Science for Nature and People—that brings university researchers together with scientists from NGOs and government agencies in the fields of conservation and development to figure out how protecting nature can benefit people, too.

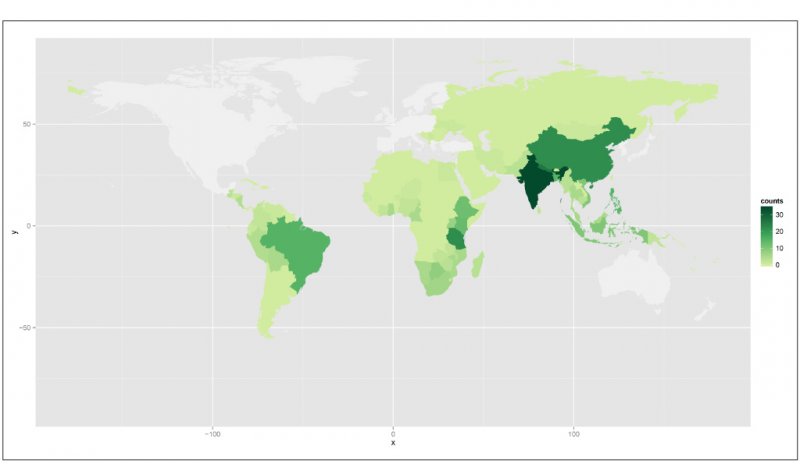

For the Nature article, Cheng and her SNaP colleagues sifted through thousands of research reports in dozens of journals to provide a reliable, user-friendly map distilling the best evidence for busy decision makers trying to decide the best course for conservation actions on the ground around the world.

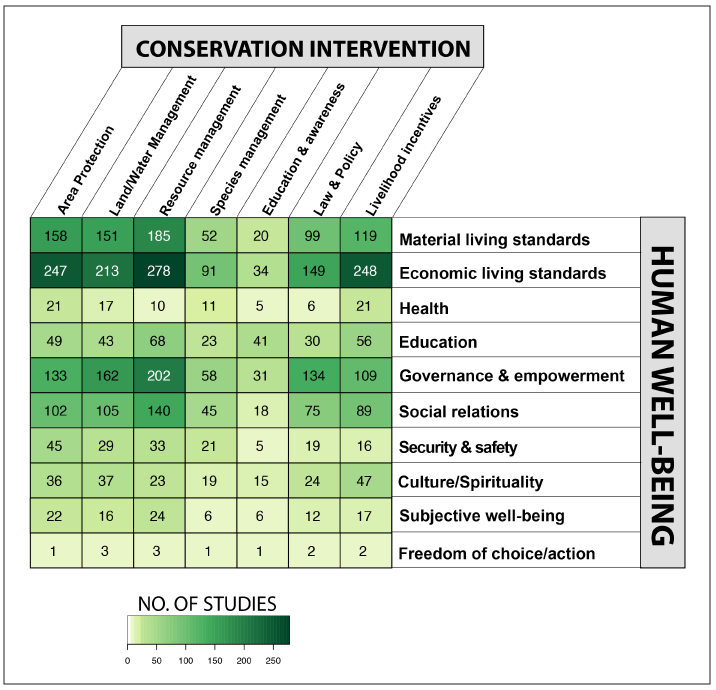

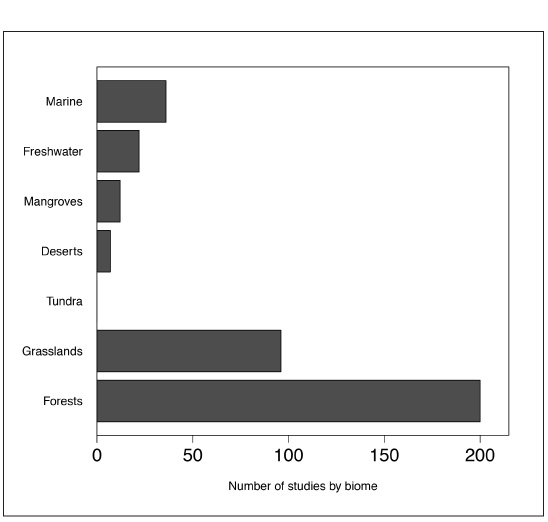

They found lots of evidence about how protecting nature affects communities economically, as well as affecting governance, and people’s social relations. But they found that a lot more research is needed on the relationships between conservation and factors such as human health, security, safety, and people’s subjective sense of well-being before robust recommendations can be drawn from the evidence.

In her own research, Cheng uses sophisticated techniques to examine genetic diversity in squid populations to inform management decisions affecting communities that depend on the fisheries from the coast of California to the Coral Triangle in Southeast Asia. IoES journalist-in-residence Jon Christensen talked with Cheng about why an evidence map could make a difference for decision makers — and why the world is awash in research papers no one seems to be reading.

Q: Why do we need a map of scientific evidence? Can’t we just Google the question and the relevant papers will pop up?

Samantha Cheng: Google is a wonderful tool and definitely can turn up rapid results for your searches. However, the relevancy of papers that pop up will depend on the keywords you use, the websites where the papers are hosted, and all kinds of other things. It takes a lot of effort to find all the relevant research and filter through the results to find the information that you need.

Having a map of all of the evidence addressing different questions about the impact of conservation on human well-being cuts out a huge time consuming step for researchers and managers. Not only does this facilitate rapid decision-making, it also helps folks draw inferences from a comprehensive set of evidence since we’ve used a systematic method to map out all of the relevant evidence.

Q: How does the evidence map help bring important papers to the attention of other researchers and policymakers?

Samantha Cheng: By creating this map, we’ve done all the heavy lifting of finding, sifting through, collating, and synthesizing relevant evidence for researchers and policymakers. Now, they can click on a specific linkage between educational initiatives in resource management, for example, and economic well-being and find all the relevant papers that have examine this relationship. This can save people a lot of time and, we hope, will encourage decision making based on synthesis of the best available evidence as opposed to one or two random papers or conventional wisdom.

Q: How do you identify the really relevant and important papers with significant findings?

Samantha Cheng: We conducted a systematic search to locate all of the relevant papers for each subject by iteratively testing sets of keywords for all types of conservation actions and all types of outcomes for human well-being outcomes. After identifying the keywords that captured the most variation in the search results, we filtered through the search by hand.

We spent an enormous amount of time reading through titles and abstracts of papers to identify the ones that documented impacts. So in total, we screened more than 35,000 titles and abstracts and from those, we identified 3,000 papers that could be relevant. We then read through those, throwing out irrelevant studies, and extracting relevant evidence that we included on the map.

Q: There has been a lot of news lately about how most academic research papers are rarely cited by other researchers and maybe rarely read. Why do you think that’s a problem? Maybe they’re just boring.

Samantha Cheng: This is a huge problem. In order for any field to progress, researchers need to know what has been done and what needs to be improved on or what gaps need to be filled. We risk wasting critical resources and funding if we answer the same questions over and over. This is also a huge problem for on-the-ground conservation and development. For example, the results of research studies on how protected areas can impact the socio-economic well-being of a community could be crucial for planning and managing a protected area.

Papers are not being read for two reasons. First, much of this research is scattered and inaccessible, in journals that are less well-known than Science or Nature or PNAS. So it is often overlooked. And most of these articles are behind paywalls so it is often inaccessible to people without academic affiliations.

Second, scientific articles can be quite esoteric. The results may not be intuitively easy to translate into guidelines for management. And there are not enough researchers who are bridging that gap between research and the application.