environmental justice, law & policy, nature & conservation

My Journey to Create the Future of Plastic Recycling

Plastic pollution is a global crisis that results in wildlife entrapment, water and food contamination, and human health problems. Globally, only 9% of plastics produced are recycled; the rest is incinerated, landfilled, or exported to developing nations where they often enter marine habitats. At the current accumulation rate, the scientific community predicts there will be more plastic than fish in our oceans by 2050.

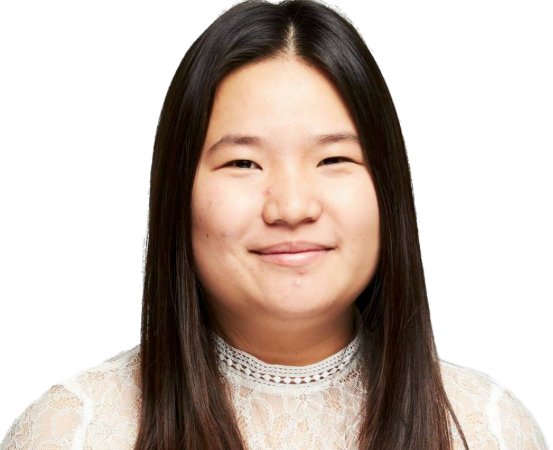

My name is Miranda Wang and I am a 24 year-old entrepreneur, environmental advocate, and inventor. I have been working with my co-founder Jeanny Yao to create solutions to the plastic problem over the past ten years.

We met each other at a high school recycling club meeting, where we collected, sorted, and sold beverage containers every Friday after school to the local recycling depot. Our volunteer hobby not only turned the Environment Club into the most profitable club at school, but it also helped us discover our life-long mission.

In tenth grade, we visited a waste transfer station in Vancouver, Canada, where I was horrified to see the amount of plastic that was going to the landfill. We were told that most plastics are actually not recyclable.

Because today’s recycling technologies can only mechanically repurpose clean plastics like PET, other common plastic packaging, made with PE, PP, or PS, lack economical outlets. So they are being landfilled or littered where they are flushed into oceans by rain and wind.

In twelfth grade, we first discovered soil bacteria that have evolved to eat plastics in the river. The bacteria have figured out a biochemical way to break apart the carbon bonds and make energy out of it, just like they do from sugar! Understanding this chemical hack was a key highlight in our journey and allowed us to see plastics in a different light.

We soon realized that since plastics are made of carbon, if we can find a way to change the chemical structure of these carbons, then not only can we break down the pollution, but we can also create new and valuable products from those carbons. If we can build a cheap enough process to make a valuable enough product, then we can create a real incentive for today’s unrecyclable plastics to be kept out of oceans and landfills.

This is more easily thought than achieved. After more years of studying and research at university, Jeanny and I founded BioCellection in 2015. Then another two years of prototyping and R&D followed, where we worked with waste experts, city governments, and industry scientists to develop a working solution that is ready to scale.

Today, our team is scaling up our first chemical invention, which is a system that can turn unrecyclable HDPE and LDPE into chemicals worth $1,600-$12,000 per metric ton. We use a catalyst that cuts carbon bonds selectively at a low temperature and no added pressure. The system creates no emissions and our prototype uses the same amount of energy as a large TV screen. Through our innovation, each metric ton of unrecyclable, dirty plastic creates $2,600 in revenue at commercial scale and is more profitable than conventional petroleum chemistry.

Next April, our scalability pilot unit will stand in the corner of our parking lot in Menlo Park, California and push through half a metric ton of plastic waste per day to serve as the stepping stone to our 5-metric ton per day commercial machine, which would still be small enough to be transported in container units.

We are working with city governments and recycling companies to intercept plastic waste before they become pollution by bringing our machines to waste plants. By embedding our innovation into the existing industry, we will not only increase landfill diversion, but we will also displace the petroleum needed to make these chemicals.

The Pritzker Prize will accelerate the realization of our vision by enabling us to develop methods to separate and purify the chemicals, so that they can serve as drop-in replacements in a new circular plastic economy.