Without electric grid upgrades, heat-related power outages in L.A. County are guaranteed by midcentury

UCLA researchers recommend upgrading power grid and smarter construction choices

By the middle of this century, severe heat waves in Los Angeles County could cause widespread power outages from the loss of up to 240 megawatts — power for nearly a quarter million homes — according to a new study by UCLA and Arizona State University researchers.

The report (PDF), the first to provide geographically specific information about the risk levels for power outages throughout the region, examines how hotter temperatures, a growing population and increased use of air conditioning could increase energy demand and weaken the electric grid between 2020 and 2060. It also provides policy recommendations (PDF) for improvements to the electric grid and smarter construction choices that could help prevent power outages.

Among them: Prioritizing investments in electric grid infrastructure where demand is expected to soar and supply is expected to decrease; and upgrading power-supply hardware like high- and low-voltage power lines, transformers and electrical substations.

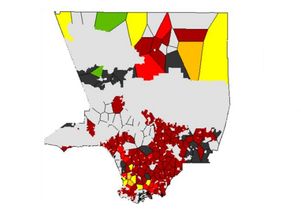

The researchers analyzed factors such as building types and power-line capacity, and produced detailed maps identifying cities and unincorporated areas that would have a high risk for heat-related power outages if greenhouse gas emissions are not curtailed and electric grids are not improved.

Without those changes being made by 2040, the report found, certain parts of Los Angeles County would be guaranteed to experience power failures at the hottest times of the year. The effects would be the most severe in the Antelope Valley and Palmdale, where increased development is planned, as well as in the San Fernando Valley, the east San Gabriel Valley, and near the county’s ports.

The report is among dozens of technical reports released as part of the state’s latest climate change assessment, which is coordinated by the governor’s office. The assessment warned that the effects of climate change in California will be worse than previously described in even the third assessment, which was published in 2012.

Stephanie Pincetl, a professor-in-residence at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability and the director of the institute’s California Center for Sustainable Communities, was principal investigator of the electric grid research. She also served on the peer-review committee for the overall climate assessment, along with three other UCLA researchers who were contributing or coordinating authors.

“The county can take significant steps to protect residents’ health as climate change continues, including changing building development policies to reduce people’s exposure to hotter weather,” Pincetl said. “For example, developers could build more densely clustered village-style communities to increase the amount of shade, and more stringent energy-efficiency building guidelines would help mitigate the effects of rising temperatures.”

Although the sharpest increases in energy demand are anticipated in parts of the county where the population is expected to grow the most, the report noted that energy demand will increase across all of Los Angeles County if greenhouse gas emissions aren’t reduced globally. Extremely high temperatures tend to worsen the performance and capacity of power generation plants and power transmission lines, the report explains.

The report focuses on projected temperatures for two time periods, 2021–2040 and 2041–2060, and compared them to 1981–2000 as a baseline. The researchers considered two potential climate futures: one in which greenhouse gases are reduced in line with the international commitments made under the 2015 Paris Agreement, and a second, business-as-usual scenario, in which emissions remain at today’s levels.

They developed scenarios for low, medium and high energy demand, based on projections for population growth, the speed of residential building replacement, and the ratio of single-family homes to more efficient multi-family homes — the factors that, even more than temperature increases, will most affect demand on the county’s electric grid.

Another problem for the energy grid is that the amount of power Los Angeles uses to power air conditioning is projected to increase dramatically the next few decades. Air conditioning typically uses 60 to 70 percent of a building’s energy. Today, only 41 percent of the county’s residential and commercial existing buildings have air conditioning, but because virtually all new buildings in the region have central air conditioning, that percentage continues to climb.

Air conditioning use will vary based on things like the proportion of multi-family homes versus less-efficient residential homes; the amount of future residential building in cooler areas versus hotter regions; and the installation of high- or low-efficiency air conditioning units.

The policy brief offers several policy recommendations to help governments and utility companies counteract the warming climate and the growing amount of electricity the county population can use during the times of highest demand, including:

- Invest in distributed energy programs, such as rooftop solar so that a power failure at one central source doesn’t affect all customers.

- Offer residents and developers incentives to use more efficient air conditioners.

- Require air conditioners installed throughout the county to function efficiently during factory testing at 122 degrees, instead of the current 95 degree standard.

- Revise outdated standards for building construction and appliance performance so that they can withstand higher temperatures, using the latest climate projections.

- Create incentives for developers to build more multi-family buildings, which are more efficient

- Create zoning that prevents new residential developments in areas at the highest risk of future outages or hottest heat waves.

The researchers also suggested tactics for both mitigating further climate change and adapting to it. Among them are a greater reliance on renewable energy sources and outreach campaigns to encourage conservation, which could help slow climate change; and improved cooling systems for power equipment, and higher standards for building insulation and thermal efficiency, which could help the region adjust to higher temperatures.

The research was funded by the California Energy Commission.

The research is in keeping with The Sustainable LA Grand Challenge, a UCLA research initiative that aims to transition Los Angeles County through cutting-edge research, technologies, policies, and strategies to 100 percent renewable energy, 100 percent locally sourced water, and enhanced ecosystems by 2050.

TOP IMAGE: Photo via freeside on flickr.com.