Gregory Okin, a UCLA geography professor, has now made those efforts a whole lot easier, having teamed with colleagues from UCLA, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and NASA to develop a powerful web-based mapping tool called LandCART, short for Landscape Cover Analysis and Reporting Tools.

The project brings together, for the first time, historical and present-day ground-level observations, climate data and remote-sensing information from satellites covering the whole of the Western U.S. A set of sophisticated algorithms processes this data into usable information about vegetation and ground cover that can be displayed simply and understandably.

“It’s a combination of an incredible set of field data, representing millions of hours of work and decades of NASA data,” said Okin, a member of the UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

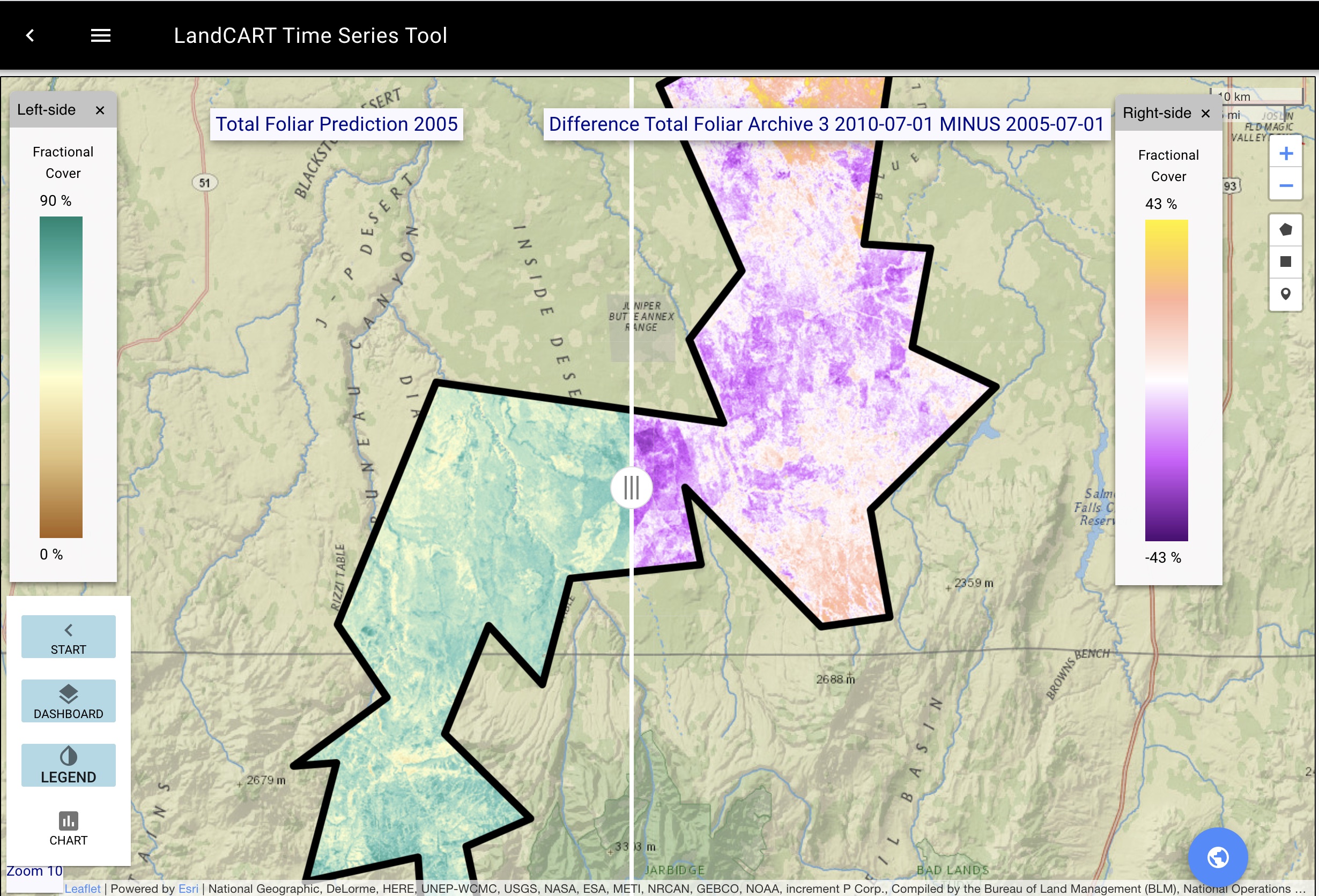

The site, which launched Feb. 15, provides a comprehensive picture of vegetation and ground cover and can display where land is covered by sagebrush, shrubs, perennial grasses or dead plant material, as well as where it has no cover. Using machine learning, the tool can also show changes in vegetation over time and perform statistical analyses on the data to help interpret the results.

Those capabilities make LandCART a boon to environmental researchers and a powerful asset to government agencies like the Bureau of Land Management and other land managers tasked with shaping policy decisions on a diverse range of issues related to vegetation, from wildlife conservation and livestock grazing to wildfire recovery. The BLM alone is responsible for 245 million acres — about one-tenth of the nation’s total land area — most of which is in the Western states and Alaska.

Gordon Toevs, chief of the BLM’s division of resource services at its national operations center, said LandCART’s ability to provide information on historical changes in vegetation — the tool incorporates nearly four decades of data — is particularly valuable.

“This information will help identify areas where potential changes in management decisions may reverse a downward trend in vegetation cover — and where BLM decisions are helping maintain desirable conditions for the enjoyment and use of present and future generations,” he said.

While LandCART will be widely used by government agencies, Okin stressed that the tool is also designed to be accessible to the general public, giving everyone — from nonprofits to ranchers to concerned citizens — better information on utilizing land properly and effectively and conserving wildlife.

For example, LandCART could be used to help protect the sage grouse. Conservationists are concerned about the bird because sagebrush, which provides essential habitat for its unique mating dances, is being replaced by invasive grasses. Mapping out ground cover over time, the tool could identify areas where interventions are most needed.

The tool could also help improve users’ understanding of how ecosystems recover after wildfires by tracking what kind of vegetation emerges in the following years — and how quickly.

But those are only a few of the possibilities, Okin emphasized.

“UCLA has created this Swiss Army knife of tools for people interested in the West to monitor conditions, make data-based decisions and manage land effectively,” he said.

Bo Zhou, a postdoctoral researcher in the UCLA Department of Geography, was a member of the research team that developed LandCART.