UCLA Counterforce Lab’s Yogan Müller publishes book on LA Aqueduct following COP21

Interview questions authored in 2024 by Elias Jabbe, former France-based researcher and current UCLA Center for Diverse Leadership in Science NSF Climate Resilience Fellow. 1) What are the main takeaways…

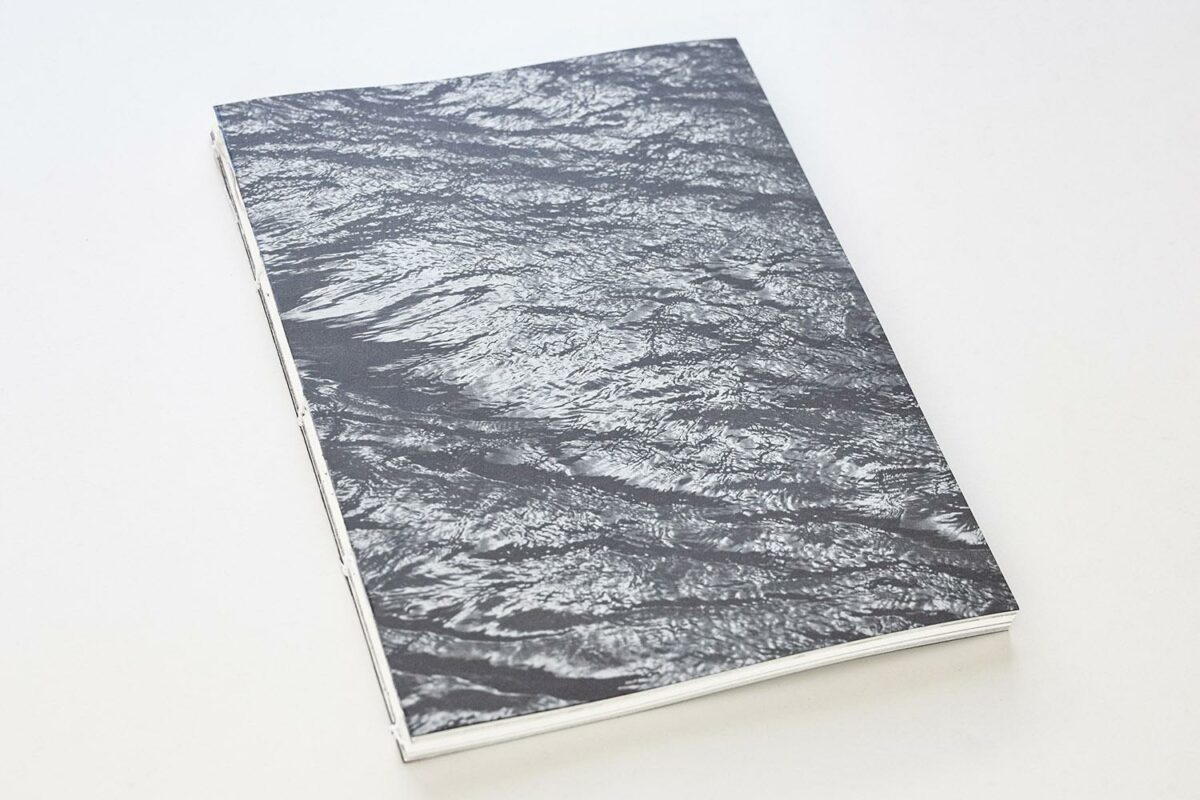

The world-traveling photographer shares the new self-published water book he co-designed with Design Media Arts students in an exclusive interview with UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. He recently received the UCLA Unit-18 Professional Development Award for this drone and water class and book.

Interview questions authored in 2024 by Elias Jabbe, former France-based researcher and current UCLA Center for Diverse Leadership in Science NSF Climate Resilience Fellow.

1) What are the main takeaways you want readers of your self-published book to understand about the source of our water here in Southern California?

First of all, I want to acknowledge my former students enrolled in the ecologically-minded studio class I taught at the Design Media Arts Department last winter 2024. Not only did they produce new projects, but they co-designed, printed, and bound this self-published book of 132 pages.

In this class, we used drones to enrich our empathetic connection to the natural world and acquire vital insights into the water-conveying infrastructure that brings life to our campus, homes, and city.

Central to our work is how much we take water for granted and yet, how vital it is to human and non-human life in our region. We shower, cook, drink, water our plants, or quench the thirst of our pets, without wondering about the available water supply or the infrastructure that makes it all work. It “just” does.

Drones and LA Water Narratives

When we began our class in January 2024, the 110th anniversary of the Los Angeles Aqueduct (LAA) inauguration was in our rearview mirror. And yet, few of us visualize the behemoth piece of infrastructure it is.

As artists and designers, give us large quantities or complex phenomena, and we will develop a visual language to bring them on a single printout. Visual synthesis is our superpower.

The LAA is this abstraction. It is 419 miles long, it has many forms and enormous quantities of water flow through the system every day.

Throughout the class, we unpacked the layers embedded in the water we consume. The construction of the LAA engendered dispossessions and erasures, which the Nüümü people in Payahuunadü (Owens Valley) experienced firsthand. In fact, it can be argued that the LAA is an aggressive form of colonization and extractivism.

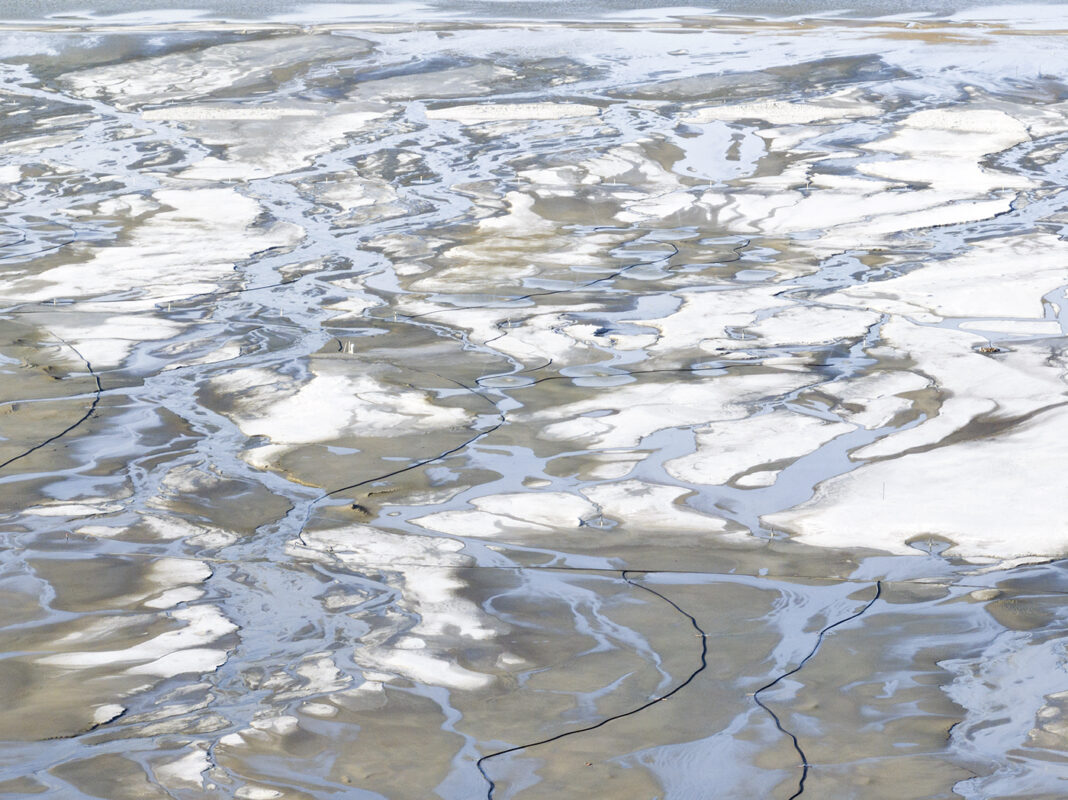

Lastly, we flew a drone to gather visual evidence of LA’s footprint, which extends far beyond the city limits. Here, Ben Lerchin’s UCLA DMA MFA graduation project YIMBI and the map titled “Los Angeles’ Uncomfortable Protuberances” were insightful. As such, large swaths of the Mono Basin and Owens Valley are LADWP property, thus part of Los Angeles. Owens Lake is a reflection of LA’s gargantuan metabolism. The lake became one of the largest sources of dust pollution in the US. Today, LADWP conducts a whole host of dust mitigation experiments.

2) How did the use of modern forms of photography like drones help you dynamically tell the story of SoCal aqueducts and expand on what you learned growing up in a family that included a professional photographer?

From a bird’s eye view, our presence as humans looks so fragile and transitory in how we inhabit and exploit the natural world.

The LAA going across the arid landscape is a good example. In my drone shots, LA’s “drinking straw” looks so small compared to the Mojave Desert’s vastness and the geological forces that have shaped this part of the country. It looks so vulnerable in the desert climate.

Drone photography is exhilarating but also quite challenging because of the huge amount of space the camera embraces. There is a long history of aerial photography that goes back to the inception of photography itself, from hot-air balloons in the mid to late 19th century, to 20th century airplanes and today’s drones. Inspired by the work of Edward Burtynsky and David Maisel, two contemporary photographers, I flew my drone to photograph the LAA in a single image, “at scale” if you will.

On a more conceptual level, I wanted to test how remote sensing could enrich our empathetic connection with the natural world. Flying a drone lets us reach inaccessible places, like steep mountain slopes in the Jawbone Canyon where the LAA turns into a large siphon. Although I am operating the drone from far away, my mind is right there, hovering over, while putting what I see on my controller into the context of the landscape where I am flying.

3) What were some of the highlights of collaborating with UCLA students for the Counterforce Lab project you are a part of at UCLA Design Media Arts department?

As part of the Counterforce Lab team, led by UCLA professor Rebeca Méndez, I have been collaborating with UCLA students in the context of the Biophilia Treehouse project.

The Biophilia Treehouse project grew from our participation in the 2019 Pando Days, a county-wide gathering of art and design schools initiated by Pando Populus and in response to LA County’s first and ambitious sustainability plan called “Our County.” We responded to goal #5: Thriving ecosystems, habitats, and biodiversity.

Over the years, we have worked with incredibly talented groups of students hailing from DMA and other UCLA departments in architecture, botany, ecology and evolutionary biology, engineering, and humanities. Some of them also joined us through UCLA’s Sustainable LA Grand Challenge. In addition, we worked with Dr. Allison Lipman and her students at the UCLA Ecology and Evolutionary Biology department to plant native plants that attract and cater to bird life. Their contributions to this multi-year public art project have been invaluable.

Working with them culminated in the inauguration of the first Biophilia Treehouse and a retrospective exhibition we mounted at the Broad Art Center in April and May 2023.

This exhibition featured research, photographs, sketches, paintings, installations, sound pieces, and videos that were, in one way or another, made by our students and that we celebrated on walls, tables, prints, and objects. As such, the exhibition celebrated the polyvocality of this project.

Currently, we are in the process of printing a booklet that will mark the fifth anniversary of the Biophilia Treehouse project. Stay tuned!

4) What was it like to collaborate with the UCLA Office of Sustainability and involve them in a chapter of your book?

UCLA Deputy Chief Sustainability Officer Bonny Bentzin generously took my class on a water tour across campus, highlighting key water reclamation projects. It couldn’t have been more timely after all the rain we received this past winter!

Together, we explored various installations but also the natural topography and creeks that flow through campus. To imagine the landscape without all the current infrastructure and buildings, and visualize the natural course of water through slopes, creeks, and floodplains was terrific. In addition, we saw how campus maintenance crews responded to the heavy rain episodes to protect buildings as well as critical infrastructure from flooding.

Bonny highlighted the numerous bioswales that help mitigate flooding and embellish our campus with native plants. In addition, she told us about the arroyo and the bridge that is now filled up to its neck by Dickson Court. It is hard to believe that in the late 1910s, a small canyon stood there and water ran through this part of our campus. Browsing through the UCLA Library Special Collections online assets, I found the picture below.

For the collective publication students co-designed and printed, I interviewed Bonny and engaged in a captivating, far-ranging conversation with her about water.

5) What words of encouragement would you like to share with other environmentally-conscious members of academia who are considering self-publishing visual content to advocate for sustainability?

A little publication goes a long way. As we enter the Anthropocene, environmental consciousness is more important than ever. A book is a magical device and a harbinger of change. It is a place of encounter, polyvocality, and a gesture of transmission. A book has the potential to spread light on complex, intersectional issues and shift our perception of sustainability, carving out ways to make the world a more sustainable and equitable place.

6) Where are some of the inspiring landscapes you have visited during your journey in academia in la francophonie at home in France and next door in Belgium and how did those travels help inspire telling California’s story through photography?

I have to say Iceland where I did fieldwork for the practice-based PhD in photography that I completed while based in Brussels, Belgium, in the late 2010s. Back then, the academic and public conversation around the Anthropocene and the ecological crisis was robust. In addition, at that time I avidly studied The New Topographics, a seminal landscape photography exhibition that became a movement in the US. Learning from their subject, mainly urban sprawl in Southern California, and their direct approach changed my life as a photographer.

In Iceland, I focused on how the sprawling city of Reykjavík encroached on the rough lava terrain of the Reykjanes peninsula, where two thirds of the Iceland population live. Incidentally, between 2010 and 2019, the number of tourists visiting Iceland rose exponentially, adding to the human footprint on Reykjanes. I wanted to photograph this.

As I photographed quarries on Reykjanes, not only did I see a manifestation of the overbearing pressure the human enterprise has in reshaping landscapes, but I also became conscious of being part of the quarrying I witnessed. Even in Iceland, a country that sells pristine nature to millions of visitors, the environment has been damaged. And, yet, the crumbling mounts I photographed are the result of my active participation as a visitor.

In essence, my work in Iceland contains the seeds of what I’ve done in Los Angeles and Southern California.

7) What are some research projects from initiatives like your May 2024 trip to IoES White Mountain Research Center that we can look forward to this year?

At the White Mountain Research Center (WMRC), I wanted to survey the LAA near Bishop and take drone pictures of the Owens River. I am grateful to WMRC’s staff Gaylene, Baz, and Steven.

The LAA is visible at multiple sites, and I enjoyed discovering them. However, after a while, taking pictures of a pipeline became uninteresting. I challenged myself to photograph how the system works: gravity. How do you photograph gravity? That was a tall order. I partially answered this question, I hope, by photographing intakes and catchments, where water ineluctably accelerates.

Taking a bird’s eye view, the Owens River bends around a volcanic shelf in the most organic forms. Its course stands in sharp contrast to the rectilinear conveying system of the LAA. In addition to this, I flew in the Owens River Gorge, a spectacular site.

In Bishop, Ben Lerchin’s words and water projects became all the more tangible, especially the idea of “protuberances” LA has in the region. I cannot tell you how many LADWP signs are posted all around town.

On the way back to LA, I felt content but saw areas where I could have insisted a little more, and notably included people. That’s for the next episode!

____

Further information:

Yogan Muller biography

Elias Jabbe biography