The Lab at 10,000 Feet

It’s 6 a.m. — first light at the White Mountain Research Center, UCLA’s high-altitude research laboratories some 300 miles north of Los Angeles. The skies are brutally scarlet, the views…

High above the clouds, the White Mountain Research Center is where scientists from around the world come to solve everything from the riddle of blood chemistry to how to save the planet.

It’s 6 a.m. — first light at the White Mountain Research Center, UCLA’s high-altitude research laboratories some 300 miles north of Los Angeles.

The skies are brutally scarlet, the views across high valleys startling in their clarity. To urban ears, there is a deep velvet silence that is both startling and profoundly soothing.

Here at the Crooked Creek Station, some 10,200 feet above sea level, most of the local brown bears and big cats are snoozing far, far below; above, golden eagles silently scan snowy outcrops for a marmot breakfast.

The winds that whip California’s third highest peak high above are not even a whisper here. This “rosy-fingered dawn” is a favorite time of day for White Mountain Research Center director Glen MacDonald, who has overseen its operations since 2012, when UCLA started managing the labs on behalf of the University of California.

WMRC, as it’s commonly called, may be the least familiar of UCLA’s satellite research centers. It’s also one of its most critical. As the center prepares to finally fully reopen after COVID-19, MacDonald is not only pondering its role in past scientific breakthroughs, he’s also making ambitious plans: He aims to tap into his deep bench of expertise across disciplines to increase the center’s role as a hub of scientific activity and discovery, and he intends to properly celebrate its 75th anniversary in 2025.

Right now, the tall Canadian is pacing around Crooked Creek Lodge — a building that in its former life was a downtown Los Angeles restaurant and was moved up the mountain on a hay truck — drinking strong coffee to battle jet lag after returning from a conference in Singapore the day before. He shakes his head, clearing the cobwebs, and admits he was not quite sure where he was when he woke up this morning. But it’s clear he’s happy to be back on White Mountain.

The dawn quiet gives MacDonald a rare moment to gather thoughts before a dozen scientists — climate specialists and astronomers, botanists and pulmonologists — spill out of their sleeping bags, fizzing with enthusiasm as they debate the day’s research challenges. How low will temperatures drop? Who has forgotten to pack what? How is the Wi-Fi?

For MacDonald, a distinguished professor of geography at UCLA since 2010, the breakfast buzz is the realization of a dream born two decades ago, when he first walked the wilderness above Owens Valley as a tourist. His young family hiked through the sub-Alpine woodlands of the bristlecone pine that distinguish the White Mountain range from the neighboring Sierra Nevada slopes. To an untrained eye, the pine may be overshadowed by the Sierra’s giant sequoias, a little diminutive and scruffy. But to its devoted following, it is a marvel of nature.

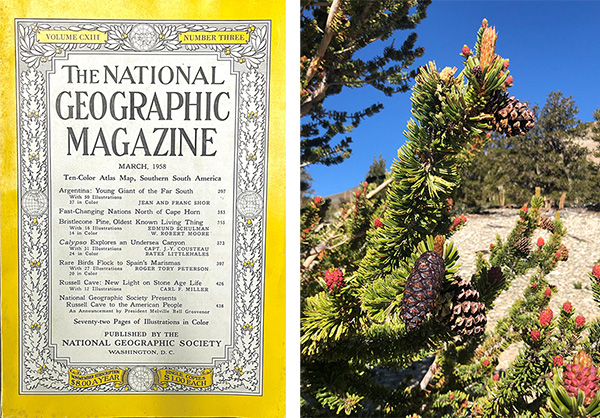

In 1958, National Geographic put White Mountain on its cover, with the proclamation that a single specimen of the pine — nicknamed Methuselah by local botanists — was, at close to 5,000 years and thus “the oldest known living thing” in the world. That pine tree is still very much alive on White Mountain, and modern genetics confirms that Methuselah (whose identity and location is kept top secret to shield it from trampling well-wishers) is indeed the most ancient tree in the known world. Its reputation still brings in thousands of tourists who walk the trails every summer, hoping to find it. Mainly, they come to exhale and get a reprieve from everyday life as they step over fallen pine timbers that, preserved in dry environs, may be 11,000 years old.

The National Geographic article marked a critical point in the evolution of WMRC. Originally opened as a U.S. Navy research center in 1948, it gradually evolved from being a test site for Sidewinder missiles into being a hub of scientific “big thinking,” complete with public open days and stylish bristlecone-themed T-shirts. As MacDonald and his crew now prepare to fully reopen WMRC for the first time in nearly four years, with lectures and community access, he wants to broadcast a simple message: “White Mountain is not just a region,” he says. “This is an entire planet.”

A History of High-Altitude Science

White Mountain, named for its permanent snow fields and white dolomite stone, is one of California’s 14 “fourteeners,” (that is, a mountain with an elevation above 14,000 feet) and is beloved by hikers and mountaineers. The White Mountain Research Center did not just materialize on U.S. Forestry Service land — acknowledged by UCLA as the homeland of the Nüümü Paiute and Newe Shoshone peoples — as today’s complete package. Its gathering places, across four elevations [see sidebar link TK], have evolved over time, with each having a different mission. Visitors arrive at the Owens Valley Station services center near Bishop, and then drive up to the Crooked Creek sleeping quarters at 10,200 feet. Two thousand feet above Crooked Creek are the more basic facilities at Barcroft Station. From there, an up-and-down, eight-mile switchback track takes you to the Summit Hut, at 14,200 feet.

Historically, much of the “hard science” done at White Mountain has taken place at Barcroft, says Daniel Pritchett, a former data manager at WMRC. He hopes that his history of the work sites, titled The Right Place at the Right Time, will be publishing during the anniversary year. “Some of the work [done at WMRC] was tough on everyone involved,” he says.

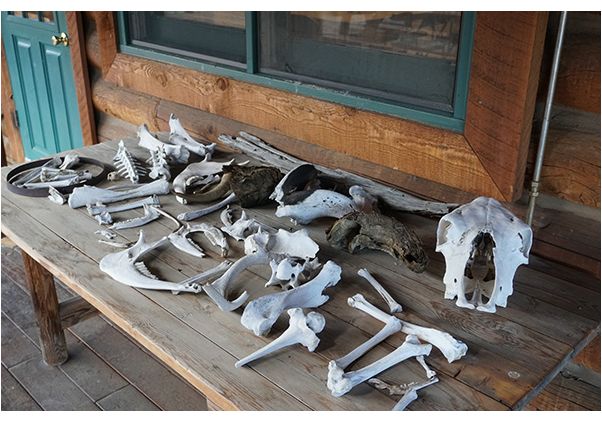

That work has included conducting altitude tests on animals, from chimps simulating space travel as part of NASA’s Mercury program to turkeys and hummingbirds and, in 1971, two harbor seals that were part of a three-month initiative called “high-altitude oceanography.”

Scientists tested themselves, too. In the 1960s, John Severinghaus, a pioneer in medical anesthesia, volunteered every morning for deeply painful spinal taps to record changes in his blood chemistry. He noted how rapid rebalancing in spinal fluids helps humans acclimatize. Astrophysicist George Smoot measured cosmic radiation at Barcroft, days he recalled during his 2006 Nobel Prize acceptance speech for his contributions to the Big Bang Theory.

Pritchett says, “White Mountain is an amazing and truly unique place for all kinds of sciences to flourish, and it has only gotten better under the guidance of UCLA, which has invested in and cared for the work here. Researchers come here from all around the world and fall in love with the place, returning year after year. It’s that kind of atmosphere.”

Into Thinner Air

Each level of White Mountain Peak offers its own adventure.

4,000 feet: Base camp is Owens Valley Station, located on former ranch land near the town of Bishop. Constructed in 1962 from redundant tungsten mining buildings, it offers a library, a public lecture space and double-wide sleeping accommodations.

10,200 feet: Crooked Creek, the first station built by U.S. Navy missile designers in 1948, was upgraded in 1989 with the addition of two cedar-log buildings — one of them the former Starlight Bar & Grill — relocated from downtown Los Angeles. Today it has fully equipped labs, sleeping quarters, a camp fire pit (though use is currently prohibited) and — most critically — Wi-Fi.

12,200 feet: Barcroft Station has been compared to an Ice Station Zebra–style Arctic outpost, where the heady effects of altitude kick in. Snack packets swell, fizzy water abruptly tastes foul and staff prepare for erratic or muddled behavior. Most visitors acclimatize after two days.

14,200 feet: The stone Summit Hut in the shadow of White Mountain Peak was constructed in 1955 for weather monitoring and communications. Usually surrounded by the snow that gives the White Mountains their name, the site is basic but open for summer day use, often by hikers. One of California’s 12 “fourteeners” (14,000-foot peaks), White Mountain Peak is more accessible than most.

Research on Higher Ground

Although situated only 2,000 feet higher than Crooked Creek, the altitude effect at Barcroft is substantially stronger. With blood oxygen levels down to around 85% (for context, hospital machine alarms flash at 93%), visitors can quickly feel woozy and discombobulated.

One immediate symptom is absent-mindedness, says Erica Heinrich, an associate professor in medical sciences at UC Riverside, who confesses she often leaves a trail of coffee cups in her wake around the Quonset huts.

Heinrich has escorted six different volunteer groups up to Barcroft to track how the body adjusts at high altitude, although hypoxia poses as many questions as answers. “Why do high-plateau Tibetans have different red blood cell counts than people living at the same altitude in the Andes? Why do superfit Olympians feel weird at Barcroft, while ordinary people adjust more quickly? What is the process of adaptation when you come down?” she says. “We know so little about so much up here.”

And like every other researcher here, Heinrich wants answers. She wants to apply the findings at her clinic in Riverside, where COVID patients’ lungs are under stress and other patients are at risk due to hearts that “are working so hard, it’s like they are up a mountain.”

The center’s location up in the clouds opens up myriad opportunities for medical research. Last summer, when I visited White Mountain, 20 pregnant ewes were being nursed at Barcroft by researchers from the Loma Linda University School of Medicine. They were monitoring fetal development issues that may eventually cast a light on human miscarriages. Feeding the sheep is a task for both scientists and WMRC staff, who describe themselves as “jacks of all trades.” Eight thousand feet below, at the Owens Valley lab complex, UCLA staffers such as botanist Gaylene Kinzy and Steven Devanzo, who is working on upgrading solar power, help maintain systems that, among other tasks, detect arsenic-laden winds arising from drained lakes and wildfires.

Part of the beauty of White Mountain is that it’s constantly evolving. Nature never stops trying to reclaim and reshape the land, remolding its features every season. Recently the center’s grasslands were threatened by a runaway Pontiac Firebird, which lived up to its name by plowing through a boundary fence to crash near the site’s former helicopter pad and catch on fire. Flames from the red (of course) sports car were extinguished just in time.

“Fires around here are caused by lightning, old infrastructure and, mostly, careless people,” Devanzo says wearily, sharing phone images of the smoking Firebird. MacDonald bursts with pride in noting how his staff throw themselves in the way of such emergencies. “These are not jobs,” he says, “for the fainthearted.”

Keeping Up With Nature

This fire-prone environment is, of course, the new normal, say Jeff Holmquist — who is famed for striding off in any direction available to shove his nose into a bug’s nest — and his colleague Jutta Schmidt-Gengenbach.

They are UCLA’s lead researchers at White Mountain, working out of a cramped lab at the Owens Valley basecamp and busy happily “trying to save the world,” Holmquist jokes.

As UCLA ambassadors, they are everywhere, all the time, all at once.

They are at municipal and water agency meetings, balancing big-city thirst and power needs with dam managers struggling to maintain antique equipment, or they’re negotiating “toilet flushes” to clear algae and keep waterways healthy for endangered amphibians. They backpack 15 miles into the high country to gather stream samples before the U.S. Forestry Service “opts for the nuclear option” of mass-poisoning brown trout, piscine predators that were airdropped into high-altitude lakes in the 1950s to attract recreational fisherman — before it was realized that they throw entire ecosystems out of whack.

The intrepid UCLA scientists also work with local tribal elders and youth, learning the traditional method of harvesting lipid-rich moth caterpillars that “taste like scrambled eggs,” Holmquist says. This involves digging trenches around nest-heavy trees, a practice that could be replicated at a larger scale to reduce wildfire damage.

That work is deeply personal: In 2015, Holmquist and Schmidt-Gengenbach were deep in the back country when a wildfire gutted their home and 40 others in the hamlet of Swall Meadows.

“February was not supposed to be fire season, but it’s always fire season now,” says Schmidt-Gengenbach. “We rebuilt, with a tin roof and new materials, but our insurance rates have gone up sevenfold.”

The pair have helped grow the California branch of GLORIA, the Austria-based organization that monitors global climate change in Alpine zones. In their spare time, Holmquist and Schmidt-Gengenbach volunteer for the Mono County search-and-rescue team, whose motto is “Where the road stops, we start.”

It’s an apt summation of the work of the entire White Mountain crew.

Looking Up and Beyond

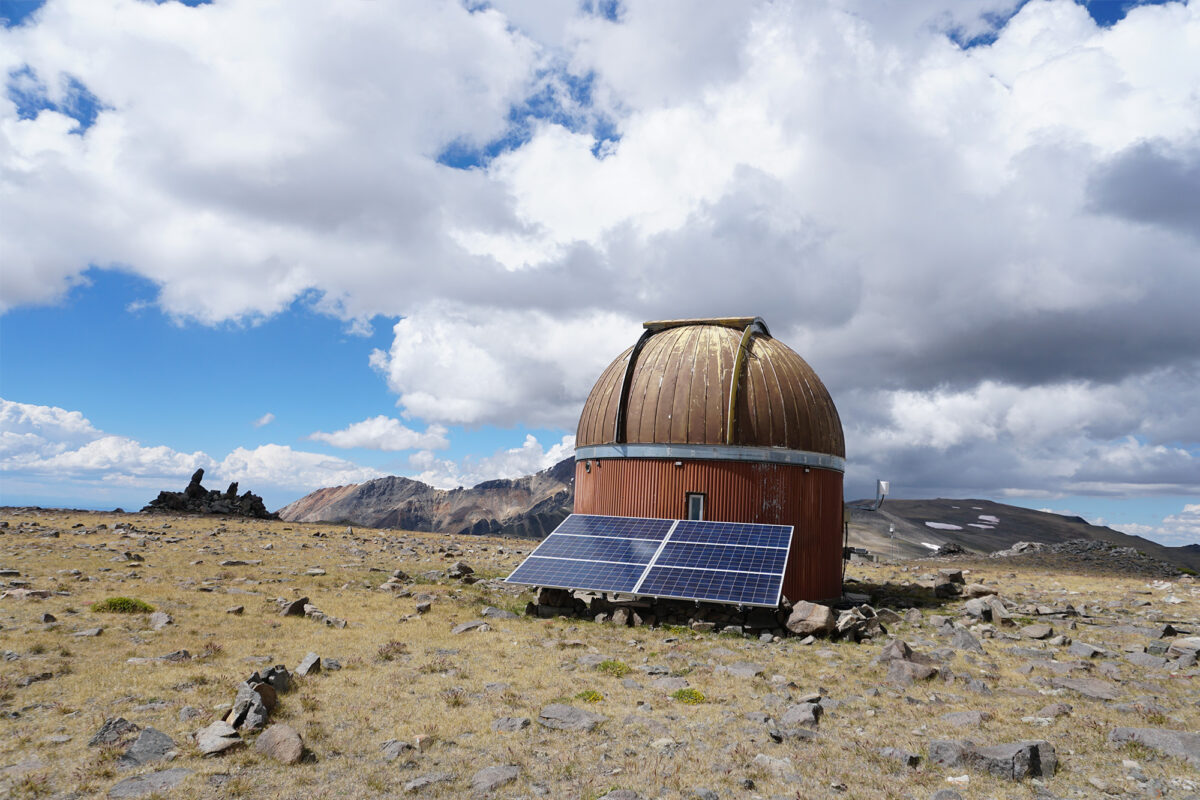

If there is one common thread that ties together all of the scientists and researchers who come to White Mountain, it is ambition. Each is on a quest for answers to a medical, scientific or environmental riddle, and they’re foraging White Mountain to find them. That also means looking out for the place. Peter Meinhold, a UC Santa Barbara research physicist who is helping to remap the night skies and advance NASA’s asteroid warning systems, would love to replace a defunct telescope dish above Barcroft.

“Getting a large dish up unpaved roads would be tough,” he admits, “but the dark skies up here are amazing for astronomers.”

Glen MacDonald, for one, has his own ideas about the next steps to take to keep WMRC evolving. “For the first few years, it was all about refurbishing the structures to UCLA standards, finding the right staff and making it home for visitors,” he says. “I want to shout about our place. What other region has such a range of zones, great basin sage, woodlands and high mountains in one place? It brings so many people together. I have seen it transform students who understand more about their place in the world. And people love to escape here.

“Over the next year, now that we are back in business after COVID, I want to deepen our engagement with local tribes and communities, maybe offer some UCLA extension courses up here,” he says. “And a gallery — we have a lot of amazing local artists. I want to bring the best of UCLA to a community far removed from Westwood, at a place where Los Angeles gets much of its water.”

So that’s everything the ambitious director wants to do. Which raises the question: What does he want to avoid?

“Lightning strikes,” he says with a laugh. “They can really ruin your day.”

And then he gets down on his hands and knees to demonstrate the best position to avoid bolts that, amid the serenity of this environment, can come out of the blue. “White Mountain is a wild place, so extraordinary, so beautiful,” he says, with a touch of awe. “But, as part of UCLA, we can find our place here.”

Published: