Ten books from 2017 that stuck with me

IoES Director Peter Kareiva’s must-reads from 2017—for holiday enrichment

These are not the “best” books of 2017, or ten books every environmentalist should read, or even necessarily books I agree with. But, in no order, here are ten books that stuck with me this year because of their writing, ideas and timeliness.

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow

Yuvall Harari

“For the first time in history, more people die today from eating too much than from eating too little; more people die from old age than from infectious diseases; and more people commit suicide than are killed by soldiers, terrorists and criminals combined.”

After conquering famine, plague and war, maybe the next step is humans as gods. Harari asks what’s next… Cyborgs? Genetic engineering? Artificial intelligence?

The Water Will Come

Jeff Goodell

Greenland is melting faster than anyone or any model expected, the Antarctic ice sheet is unstable, and the water will come. Goodell speaks to politicians, developers and ordinary people from Miami to Lagos, weaving one of the most trenchant climate sagas ever written. It reads like science fiction, but features science punctuated by interviews with Obama and a speech from Miami’s mayor assuring an audience “we’re going to have innovative solutions to fight back against sea-level rise that we cannot even imagine today.” What Goodell does so well—and which most science writers fail at—is populating his book with memorable people.

The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone

Steven Slomian & Philip Fernbach

We think in groups. And most of us are not as smart as we think we are. Slomian and Fernbach argue this is a result of us being a social species that evolved to thrive via collaboration—with different individuals mastering different knowledge. Zipping up your jacket without really knowing how a zipper works is probably okay. But having a firm idea on how to address climate change because your social group has the same idea produces partisan enclaves resistant to new knowledge. There is no obvious solution to our hardwired tendency to groupthink. But perhaps being aware of it will help.

Coach Wooden and Me

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Coaching, mentoring and teaching can yield lifelong relationships that simultaneously constrain and liberate. This story, told by the NBA’s all-time leading scorer, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, reveals how a seven-foot-tall black, jazz-loving hipster from Harlem could relate to John Wooden, “a 55 year-old five-foot-ten-inch white man from a hick town in Indiana” … an “odd-couple sitcom waiting to happen.” Together, they invented and perfected the sky hook, an unstoppable shot of remarkable skill and grace. In the background is racism and the question of when quiet decency is not enough. Kareem and Coach Wooden shared a love of reading, beautiful words and a sense of team. One story in chapter four ends with the line “No one eats unless we all eat.”

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

Arundhati Roy

Politics and personal, children and violence, and the fragmented society of India permeate this novel. No one writes about personal tragedy and sacrifice as well as Arundhati Roy. It has been twenty years since she wrote _The God of Small Things_. In that time, Roy has been an activist and an outspoken social and political critic. Her politics shine through in this most recent offering, but Roy’s devotion to humanity makes it the most provocative novel of 2017. Vivid depictions of violence in Kashmir and the forced exodus of homeless people from cities make last month’s expulsion of beggars for Ivanka Trump’s visit seem entirely normal—even expected. Roy’s India is quite different from the India that remains a darling of global investors and entrepreneurs.

A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived: The Human Story Retold Through Our Genes

Adam Rutherford

Best-selling science books are often filled with stories of the latest discoveries, but give the reader too little credit and keep things too simple. By mapping and describing our DNA, the DNA of Neanderthals, and the evolution of skin color and lactose tolerance, Rutherford teaches us about our history, our prejudices, and genetics. He makes it clear that there is little evidence to support the idea of criminal genes that control our behavior. I was stunned to read about a Tennessee man who shot a woman eight times, killed her, then bludgeoned her friend and his wife to near death, cutting off her fingers—but was given leniency because of a supposed criminal gene. No less unscientific is the idea that the prevalence of African-Americans on NBA all-star teams is based on a racially-linked genetic advantage. Faulty genetics and misbegotten evolutionary stories about humans have long been used as tools for racism and colonial persecution. Rutherford would have it otherwise.

The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics

David Goodhart

Several 2017 books attempt to explain the rise of Trump. A few, including _The Rise of the Outsiders_ by Steve Richards and _Win Bigly_ by Scott Adams, offer good insights. But the one that stuck with me most is Goodhart’s analysis of Brexit, in which Trump is only cast in a supporting role. Goodhart’s central point is that the politics of culture and identity have overwhelmed the politics of the left and right. There is faith, flag and family versus tolerance, mobility and novelty. Some of us are comfortable anywhere and see a global world—we are the Anywheres. Others are rooted in place, and are not comfortable with change—they are the Somewheres. There is no question globalization has benefited many, and most especially the Anywheres, but the Somewheres (such as steel-workers in Ohio or farmers in Scotland) have often been left behind. Many Anywheres think history is on their side, and that after the elderly Somewheres die out, all will be good. Maybe. A smarter approach would be to give a voice to the Somewheres.

How We Talk

R.J. Enfield

Conversation is a miracle. How is it that we do not talk over one another, interrupt or have long pauses? It turns out there seem to be universal rules that apply to conversations across cultures. The most important is “no audible gap and no overlap.” Conversations flow because most speaker transitions occur within 200 milliseconds—faster than the blink of an eye. Since it takes half a second to formulate what is going to be said and then start to speak, we must be predicting in advance that the other speaker is about to cede their turn. The cues include changes in pitch and intonation. Sometimes people are spoken over because they simply do not give the right cues. This book is filled with fascinating rules governing how we talk, and in turn insights into why conversations can fail so miserably. One unstated rule is that in conversation we are expected to gloss over details to move things along. When someone then probes for details, it often feels awkward or even aggressive. Armed with this book, I started seeing clearly how some people in my workplace just do not jibe because they cannot seem to get their gaps, pauses and transitions down.

Everybody Lies: What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are

Seth Stephens-Davidowitz

How we respond in exit polls and what we tell our doctor or spouse (stated preferences) often stands in contrast to what is revealed by Google searches or activity on entertainment sites like Netflix (revealed preferences). The regions with the most supporters of Donald Trump tend to also have the most Google searches for what “n” word? As the media celebrated a post-racial America on Obama’s election eve, Google searches that evening revealed the opposite. Of course, big data is not just about lying—it is about what can be learned by putting data sets together. When you analyze hourly FBI crime data, box-office numbers, and the amount of violence in every film from the parental guide site kids-in-mind.com—you find out that crime drops on weekends with very popular violent movies. For sure, there is a lot of junk in big data, but there are also remarkable opportunities for ingenious economists and social scientists (or predatory advertisers and repugnant narcissists).

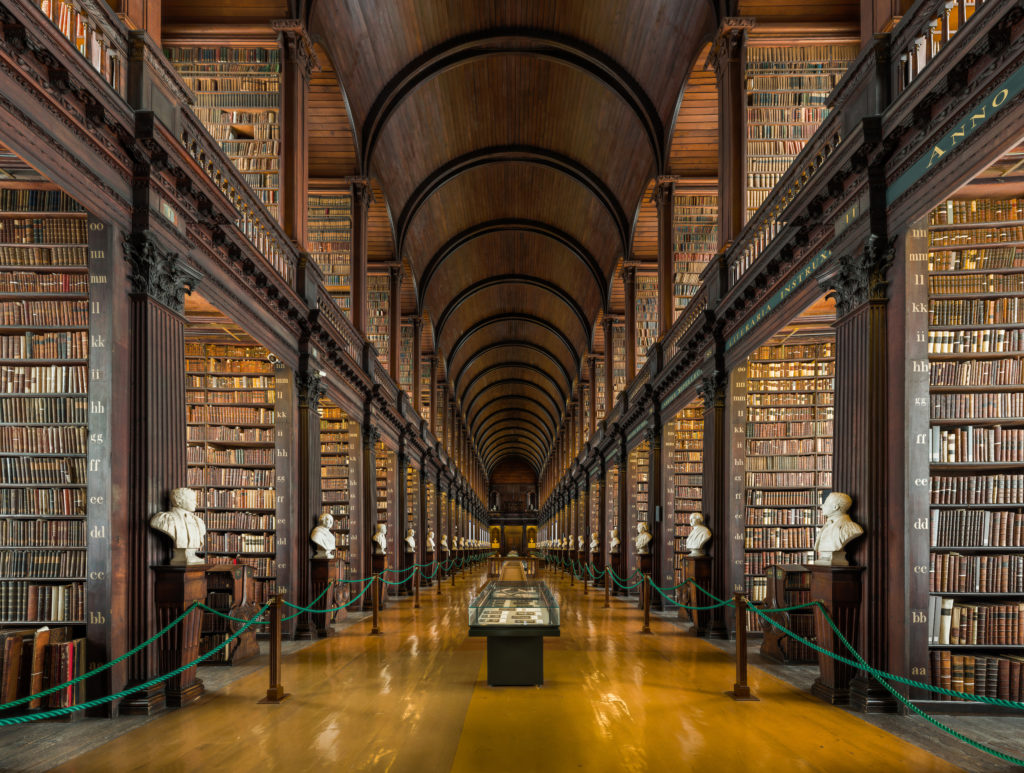

TOP IMAGE: The Long Room of the Old Library at Trinity College Dublin. | Photo by David Iliff.

Published: