The science behind “An Inconvenient Sequel”

The decade-plus since the first movie has seen record-breaking climate changes and extremes

In theaters for one month now, “An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power” has focused public attention upon the increasingly stark effects of global warming around the world — and the ongoing economic and political debates that will ultimately determine the fate of Earth’s climate future.

Against the backdrop of the unprecedented flood disaster currently unfolding in Houston, Texas, the film serves as a timely reminder of the sometimes tragic consequences when extreme weather, urban development and the effects of climate change collide.

It’s hard to believe that more than a decade has passed since “An Inconvenient Truth” first brought global warming to movie screens in 2006. The topic of climate change remains very much in the news, and we’re still struggling with the same public discourse — with familiar charges of scientific bias and media misrepresentation. It might be easy to conclude that little has changed over the past 10 years.

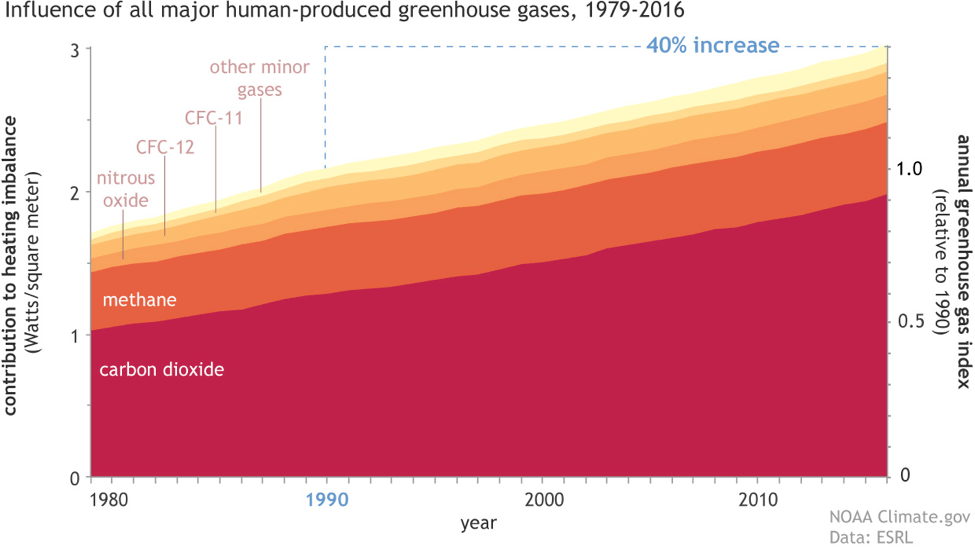

Yet, the reality is that astonishingly much has changed — and not in the direction the creators of Inconvenient Truth would have hoped. Between 2006 and 2017, the Earth’s heating imbalance increased by nearly 20 percent, a direct consequence of the continued rise in human greenhouse gas emissions. While that might not sound like much, it represents alarming growth in an imbalance that’s already larger than any in the past million years or more. During the same period, the Earth experienced both its warmest decade and warmest year on record. In fact, eight of planet Earth’s ten hottest years on record have occurred since the premiere of “An Inconvenient Truth.”

We all know what heat does to ice. So perhaps it shouldn’t be a surprise that there’s been less ocean ice in the Arctic every year since 2006 than in any year prior — a decline that has accelerated since the early 2000s. And it is not just ocean ice that is melting. Over that same time interval, nearly 2,500 gigatonnes of the Greenland ice sheet melted into the Atlantic Ocean. For perspective, that’s enough water to fill half of Lake Michigan, or Lake Erie five times over.

Lastly, rising sea levels have already started to inundate low-lying coastal areas on a regular basis — and during extreme storms, coastal flooding in some cities has produced record-breaking damages.

In short: global warming has progressed as was foretold in “An Inconvenient Truth,” and in a manner strikingly consistent to that which scientists have projected.

And it’s not just the Earth’s climate that has changed dramatically in the past decade or so — the science of global warming has leapt forward as well. While our basic understanding of the greenhouse effect has remained largely unchanged for over a century, scientists have made major breakthroughs in linking global warming to certain kinds of extreme weather events. The emerging field of “extreme event attribution” has confirmed what some scientists hypothesized decades ago: that the Earth’s warming atmosphere would eventually yield stronger, longer-lasting, and more frequent extremes of temperature and precipitation. Today, the link between climate change and heatwaves, droughts and floods is no longer theoretical — it’s an observable fact, and it’s having a material impact on people, economies and ecosystems across the globe.

Present-day greenhouse gas concentrations will continue to alter global climate for decades (and perhaps centuries) to come. Taking into account basic scientific principles and the formidable inertia of our carbon-intensive society, it’s clear that a substantial degree of additional warming is unavoidable — so building a society resilient to a warmer, more extreme climate is an urgent necessity. But the enormity of the changes taking place all around us should not become an excuse for inaction. A rapid and global shift toward renewable energy can greatly mitigate future warming in the decades to come — a transformation that, while dramatic, remains within the range of technological possibility. We still have a window of opportunity to avoid a future climate that is truly unrecognizable. It’s our hope that, a decade from now, we’ll be able to look back and know that we made the choice to bend the carbon curve.

Top Image: Sea ice in front of Bylot Island, Canada. | Photo by Paul Gierszewski.

Published: