Right-sizing the feast: Archaeological insights from the COVID-19 pandemic

In a holiday season that will feature smaller dinner tables and celebrating in different ways, it’s worth reflecting on how feasting habits have changed over the years and how the…

The ancient world was full of medical and economic crises — it’s just our luck to be experiencing one ourselves in 2020.

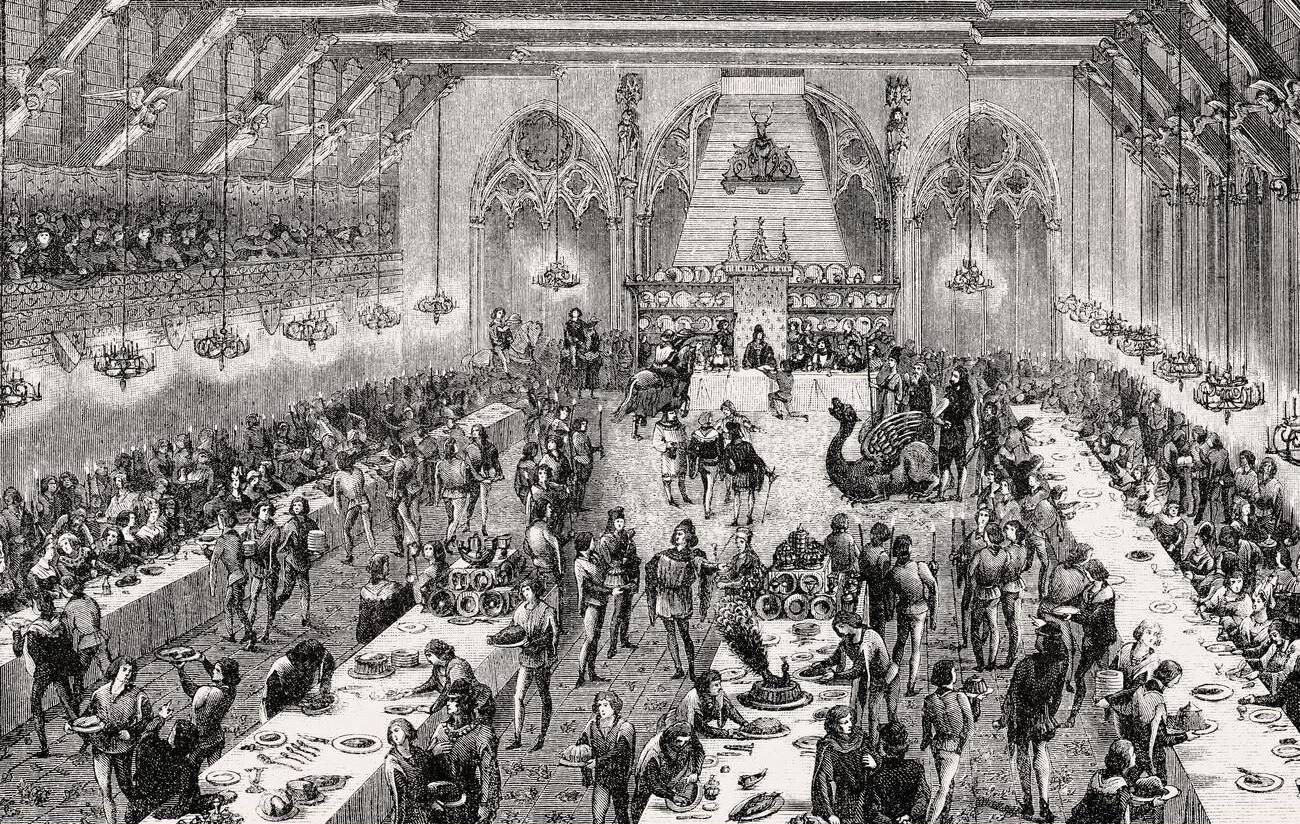

In a holiday season that will feature smaller dinner tables and celebrating in different ways, it’s worth reflecting on how feasting habits have changed over the years and how the material abundance of a feast is a clue to its importance. Whether your ideal table features a turkey, a tureen or a loving heap of latkes, you’re sure to feel a little shortchanged this year when your holiday meal looks the same size as any other day.

Ordinary meals have changed too — gone for now are the communal tables shared with strangers, the cheerful jostling at the food truck, and the box of doughnuts at the office. But it’s the holiday meals that make us feel especially deprived, given that the novel coronavirus that emerged on the global stage at the beginning of this year continues to dramatically impact our interconnected realms of work, worship, family, recreation and sociability.

In our UCLA graduate seminar Human Complex Systems in the fall of 2020, we sought to evaluate ways in which national and international foodways have been affected by the coronavirus epidemic. We looked at agricultural production, distribution, consumption and discard, and at questions of food justice and food insecurity in the present and in the future. We also looked at how the pandemic has provided moments in which our assumptions have been called into question, leading us to ask why certain patterns of behavior had become so thoroughly and subtly encoded into everyday life.

It was one set of headlines in particular that brought our warm and engaging conversations into a special focus: the newspaper articles, starting in mid-November, that “Turkey farmers fear that, this year, they’ve bred too many big birds” and “With tiny turkeys in demand, sellers are getting creative.” The growth of Thanksgiving as a holiday in the United States was paralleled by a growth in the girth of our turkeys. Suddenly, however, that big bird was not a welcome presence but a logistical nuisance, as well as a reminder of what had gone wrong with management of the pandemic and a sad symbol of the kind of meals we were not going to share for the holiday.

This year’s quirky revelation about animal sizes and their implications led us to re-examine how we analyze both daily and special-occasion meals in the past as well. When our ancestors were hunter-gatherers, “right-sizing” was just a matter of trapping or spearing an animal and taking home the choicest cuts; because the animal was wild, humans had made no investment in its growth and development. While waste might have been measured in symbolic or spiritual terms, it was not calculated on an economic basis. These perceptions changed when our ancestors started raising animals for food around 10–12,000 years ago, taking over the life and lifespan of the range of beasts that still provide most of our meat today: cows, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens — and turkeys. With domestication, humans’ birth-to-death investment in every animal became timed for some optimal quality such as taste through the culling of juveniles (suckling pig, lamb, veal), by letting animals reach full size to provide traction (horses, oxen), or by allowing mature females to reproduce which resulted in milk for dairy products.

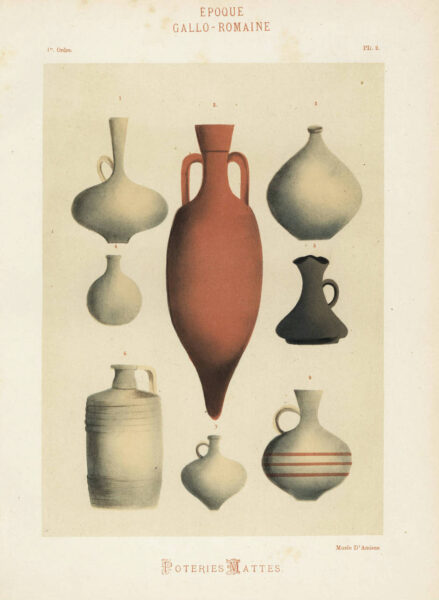

It was not only the animals themselves that were “right-sized” through careful investments of time and energy, but also the containers, cooking utensils, storage vessels and processing equipment associated with everyday foods and ceremonial feasts. As an archaeologist, I often find ancient containers that were standardized not because of government decrees about size, but because manufacturers, distributors and consumers alike had an idea of the most appropriate containers for different foods. Some of those vessels seem awkward to us now, such as the Mediterranean amphora with its big conical foot and two elongated handles that was ubiquitously used for wine, olive oil and grain, and found on archaeological sites from Britain to India. Too big to be the focus of a family dinner, they lead us to realize that a big storage vessel means a commitment to finishing the contents or decanting them into smaller vessels before the contents spoil.

The notion of right-sizing is complicated enough for daily meals as families grow or shrink in size over the course of a lifetime. It becomes particularly noticeable during once-a-year holiday traditions. Big turkeys were a problem not only in production and distribution, but also preparation. In most celebrations, an experienced older family member orchestrates the special dishes and wrangles the bird. Cooking requires the confidence to scale up spices and cooking times for the extra-large unit of meat that is the focus of a once-a-year event. The bird not only benefits from the lore of cooking that constitutes an oral history, but from the special equipment that often is kept in the spacious cupboards of an ancestral home: the roaster, the baster, the lacing pins, the oversized platter (or deep fryer!) that only comes out on holidays.

Our foray into the world of ancient right-sizing is a question larger than one holiday, and addresses the function of food at the nexus of nutrition, sociability and the ever-present shadow of crisis. Archaeologist Savino di Lernia showed that, in the Sahara Desert 6,000 years ago — as the climate started to become warmer and drier — people sacrificed prime animals in a cattle cult that may have encoded wishful thinking for a return to better times. Other ancient crises, like the demolition of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 CE that ended the Jewish practice of animal sacrifice, were moments in which expectations came to a sudden halt. And we can identify slow movements of change such as the development of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent in which people increasingly disavowed animal sacrifices and meat-eating in favor of other forms of community meals.

In our current moment, the thought of too much food seems like our own form of wishful thinking, a luxury that food-insecure people are striving to attain. Yet right-sizing is also a concern for food banks and other institutions that are trying to help people mitigate the effects of job losses and economic uncertainty. Does the expertise of cooking daily meals based on frequent trips to the grocery store translate to the ability to manage a large bimonthly box of groceries? To what extent are food suppliers able to match recipients’ needs and culinary identities that include vegetarianism, veganism and medically-restricted diets? Staccato vacillations of abundance amidst hardship can lead “too much of a good thing” as noted by food archaeologists Amy Bogaard and Kathryn Twiss, who addressed this dilemma by looking at the food storage capacities at ancient Çatalhöyük in Turkey, which was one of the first settlements to experience the challenges of the transition to a settled agricultural lifestyle.

The idea of right-sizing compels us to think beyond a single meal or a single crisis to envision how entire food systems are configured at scales from the individual and the household to entire communities and cultures. What counts as an appropriate amount of food is measured not only by nutritional adequacy but also by every aspect of production, distribution and consumption. As this year’s holidays are upon us, we recognize the intricacies of our own food systems. And, as always in the study of human societies, a little newspaper headline can turn into a big research question that lets us transform our own moments of sentimental loss into new ways of looking at the past.

Written in conversation with seminar participants Steven Ammerman, Eden Franz, Ariana Gunderson, Zachary Moss, and R.J. Sinensky.

Top image via Alamy.