Passion for environmental justice fuels urban oil drilling study

A UCLA student-led survey uncovered stark disparities in public health outcomes for L.A. neighborhoods with oil and gas drilling.

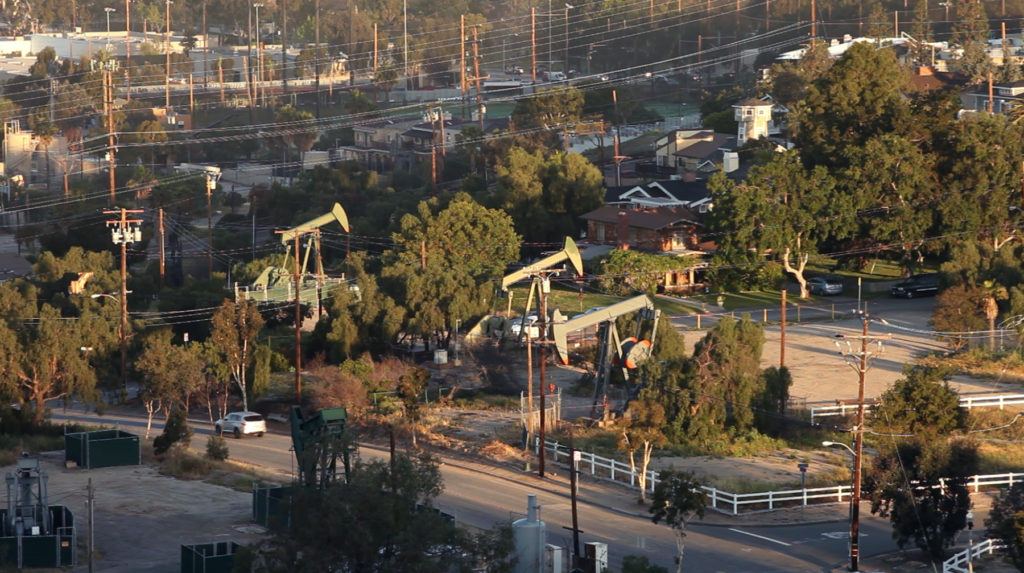

It’s L.A.’s dirty little secret: 6,717 oil and natural gas wells operate within the Los Angeles Basin — even in residential communities.

This spring, six UCLA seniors surveyed residents of one such community, Wilmington, to find out how urban oil drilling affects their lives. They conducted dozens upon dozens of interviews, hearing stories about chronically sick family members and friends. The process increased the students’ desire to empower the community, whose residents reminded them of people they grew up with.

Wilmington is located in the southern part of L.A. County, south of Compton and directly west of Long Beach. To gauge the health and social impacts of urban drilling, the students repeatedly fanned out with clipboards. The survey showed that Wilmington is 92 percent Latino, a number slightly higher than 2010 census results indicated. Forty-five percent reported having less than a high school degree, and only 22 percent reported an income greater than $30,000 per year.

The students’ mission was scientific and data-driven, but human beings can’t be reduced to statistics. Unsolicited, residents shared personal stories about children or relatives who developed asthma and other health problems. One woman recalled needing to visit the hospital after a drilling site emitted a foul odor for five hours straight.

“I feel anger and sadness,” said a tearful Anakaren Andrade. “For me, this project has always been very personal. I come from South Central, so I identify with all the people here. It’s basically the same as my neighborhood.”

On June 3, the UCLA students gave back to Wilmington, presenting their project results at a local library. Locals filled the room to learn what is happening around their homes, picking up fact sheets with findings and information on how to file complaints and report violations.

In their research, the students compared the experiences of people living in Wilmington to those of residents of West Pico, a neighborhood south of Beverly Hills that is 88 percent white, where 77 percent of adults possess a college or professional degree, and where 58 percent of those surveyed reported an annual income higher than $30,000.

Both communities live among active oil drilling sites. More research is needed, but the survey revealed a tale of two neighborhoods, tinged with racial injustice.

Wilmington was disproportionately affected by health problems associated with drilling exposure: five times more coronary heart disease and 3.3 times more throat infections. Residents were also 10 times more likely to experience chest pain or tightness, and 3.5 times more likely to have dizziness and nausea or vomiting.

The students isolated the drilling’s effects by sampling only within a quarter-mile radius of single, active wells. A control group in Pacoima with no active drilling sites returned results similar to West Pico’s, despite having demographics similar to Wilmington. In total, they knocked on approximately 1,500 doors to get 150 completed surveys.

“It seemed even before we started that there was some environmental racism going on, because there are significant visual differences between the two places,” Andrade said. “In West Pico, you only see one oil facility. In Wilmington, you see a lot of them.”

In Wilmington, residents were more aware that fossil fuel extraction was taking place, with wells often operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week. But that has not translated into an ability to do something about it. People in that community are focused on more immediate challenges, Andrade said, such as “being able to pay rent every month or surviving the education system.”

In West Pico, people were less aware of the drilling site’s existence — likely because of its operation and appearance, said UCLA team member Margaret Rubens. “It is entirely enclosed in a building, so you wouldn’t even know it is there, and they have strict regulations on the hours that it is allowed to operate.”

The L.A. Basin is the United States’ third-largest oil field and the largest urban one. More than 580,000 people live within a quarter mile of drilling sites. The easiest oil to reach is long gone, so companies employ soil acidizing, which uses hydrofluoric acid and other toxic chemicals to extract what remains.

The student project is part of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability’s senior practicum, a yearlong program that pairs small groups of undergraduates with nonprofit organizations, businesses and government agencies to work on real-world environmental problems. For this project, the students partnered with Stand Together Against Neighborhood Drilling, or STAND-L.A. The organization describes itself as “an environmental justice coalition of community groups that seeks to end neighborhood drilling to protect the health and safety of Angelenos on the front lines of urban oil extraction.”

Despite forming just three years ago, the coalition has already seen progress at city hall. On April 19, L.A. City Council President Herb Wesson introduced a motion directing the city to study creating a buffer zone between oil and gas drilling sites and homes, schools, churches and healthcare facilities — a necessary first step for bigger changes to happen, according to a STAND-L.A. statement.

The students’ findings will help inform that process, said Bahram Fazeli, a STAND-L.A. research and policy specialist who oversaw the project along with UCLA faculty members Peter Kareiva and Moana McClellan.

“Every bit of information helps,” Fazeli said. “And it’s serving the community that UCLA is a part of in the process.”

Most of the UCLA students said they came from communities similar to Wilmington — and they leveraged that natural connection to encourage reluctant residents to participate in the survey.

“If they can trust you right off the bat, that makes a huge difference in how they are going to respond or how willing they are to respond,” said UCLA’s Lizet Pantoja-Perez, who grew up in the east San Francisco Bay Area. “I joke, I talk how I would talk to my parents and my uncles.”

Erick Zerecero Marin, who has lived in Mexico City and Lawndale, said he came away with a sense of confidence and pride.

“We spoke to one retired woman who said her community was not safe in a bunch of ways,” Zerecero Marin said. “At the end, she looked up and said ‘I’m really proud that you are doing this for the community.’ They feel happy that there are people in higher education who can reflect themselves and do work for them.

The students will present their final report on their findings at a Saturday, June 10 event at the Fowler Museum at UCLA, along with other teams who researched everything from sustainable ebony production to whether kelp forests offer sea life refuge from ocean acidification.

Top image: UCLA students Margaret Rubens and Tony Carrera interview a Wilmington resident.

Published: