Nearly half of Colombia’s culturally important plant species lack conservation protections

Nearly half of these culturally significant plants lack the conservation safeguards needed to ensure their survival, according to a new study published in Ecosystems and People. The research, led by…

From lush rainforests to high-altitude páramos, Colombia’s landscapes are home to more than 6,000 unique plant species. Many of these plants are woven into the fabric of the nation’s culture, fueling artisan traditions that stretch back millennia.

Nearly half of these culturally significant plants lack the conservation safeguards needed to ensure their survival, according to a new study published in Ecosystems and People.

The research, led by Katherine Hernandez, a Ph.D. candidate at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, examined 76 plant species that are integral to traditional Colombian crafts. It revealed that 46% are not listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List—a global database that identifies and prioritizes at-risk species.

Without this designation, these plants are effectively invisible to the international conservation community, leaving them vulnerable to habitat loss, overharvesting and climate change, Hernandez said.

Colombia’s artisan sector contributes around 2% to the nation’s annual GDP, with over 350,000 artisans reliant on native plant materials. Yet, as plants like the wax palm, or Ceroxylon quindiuense—Colombia’s national tree—face overharvesting, artisans are forced to adapt by using alternatives that may lack the same cultural resonance.

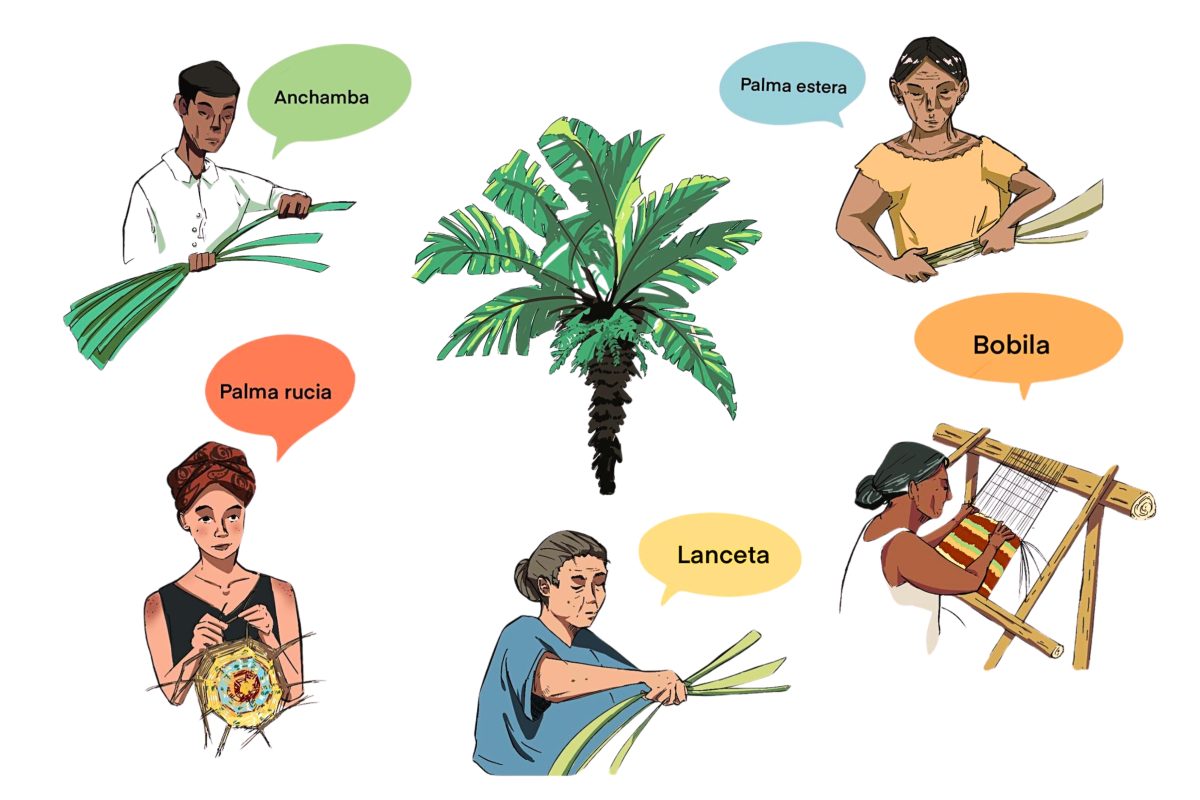

The study examined the cultural importance of plants by analyzing their common names. A single species might be known by dozens of names, reflecting its deep ties to local traditions. For example, the small palm Astrocaryum malybo is known as Palma Estera or Anchamba, depending on the region and its use. Plants with fewer names, however, often lack visibility in conservation circles.

“One species had about 50 names, some had more than 20 and others only had one,” Hernandez noted. “Their loss would be widely felt. But even species with just one name can be critical to a specific group, and their decline could devastate local traditions.”

The study revealed a concerning disparity: plants with fewer names are often absent from both national and international conservation lists. While the IUCN Red List prioritizes biological factors like population trends and geographic range, it largely overlooks cultural significance—a gap researchers say needs urgent attention.

“Adjusting the Red List criteria to include cultural uses would be transformative,” said study co-author Alejandra Echeverri, Colombian professor at UC Berkeley and nominee for the 2021 Pritzker Environmental Genius Award. “It would ensure greater visibility and protection for plants integral to crafts, medicines and rituals, many of which are culturally irreplaceable.”

Artisan traditions in Colombia stretch back over 3,000 years, with techniques passed down through generations of Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities. Basket weaving, pottery and textile production each embody regional identities and are integral to Colombia’s cultural legacy.

Felipe Zapata, co-author of the study and co-director of UCLA’s Center for Tropical Research, explained that the decline of culturally significant species disrupts traditions and identities.

“Colombia’s wax palm, for instance, was historically used in Palm Sunday celebrations until it was heavily impacted by overharvesting,” Zapata said. “Now, communities have had to adapt by using alternative materials to reduce pressure on the species, illustrating how the risk of extinction can disrupt cultural practices and prompt changes to protect biodiversity.”

As Colombia navigates the intersection of biodiversity and community needs, the study underscores the potential for conservation models that integrate cultural and ecological priorities. Collaborative efforts involving Indigenous groups, local policymakers and international conservation organizations could pioneer new strategies for safeguarding these vital plants.

The stakes are high—not just for Colombia, but for the global community. Protecting these plants means preserving the intricate relationships between nature and culture, ensuring that future generations can continue to weave the stories of their heritage into the fabric of their lives.

“The loss of a plant, even if it’s not globally extinct, would feel like a loss of identity for some communities,” Hernandez said. “Conservation can only be effective—and lasting—when it works hand-in-hand with the people who have the closest ties to the land and its resources.”

This article features an image courtesy of Zuahaza, a women-led artisan cooperative dedicated to preserving Colombia’s rich weaving traditions and empowering local communities. Explore their work and support their mission by visiting their website.

Published: