Natural justice

Just ask Osceola Ward, a UCLA graduate student who teaches disadvantaged kids to advocate for their communities and their futures. Ward wanted to be a lawyer, but his plans changed…

Environmental issues are social justice issues.

Just ask Osceola Ward, a UCLA graduate student who teaches disadvantaged kids to advocate for their communities and their futures.

Ward wanted to be a lawyer, but his plans changed during a class action suit against Chevron. In August 2012, the oil giant’s refinery in Richmond, California caught fire, sending a plume of toxic, black smoke into the air. As an intern with the firm that filed the suit, Ward answered calls from people affected by the disaster.

“People complained about bloody noses and mothers cried on the phone,” Ward says. “I had to record them verbatim—six hours per day, for months on end.”

Chevron eventually pled no contest and paid $2 million to settle the case, but the experience affected Ward deeply. He refocused his career toward environmental justice.

After finishing up a bachelor’s degree from Howard University, he came to UCLA for graduate study. He joined the Leaders in Sustainability certificate program as he worked towards a master’s degree in Africana Studies. The sustainability program brings together students from diverse fields of study to focus on environmental problems. Each student devises a leadership project that has measurable outcomes. Ward’s project focuses on empowering Black communities to advocate on environmental issues.

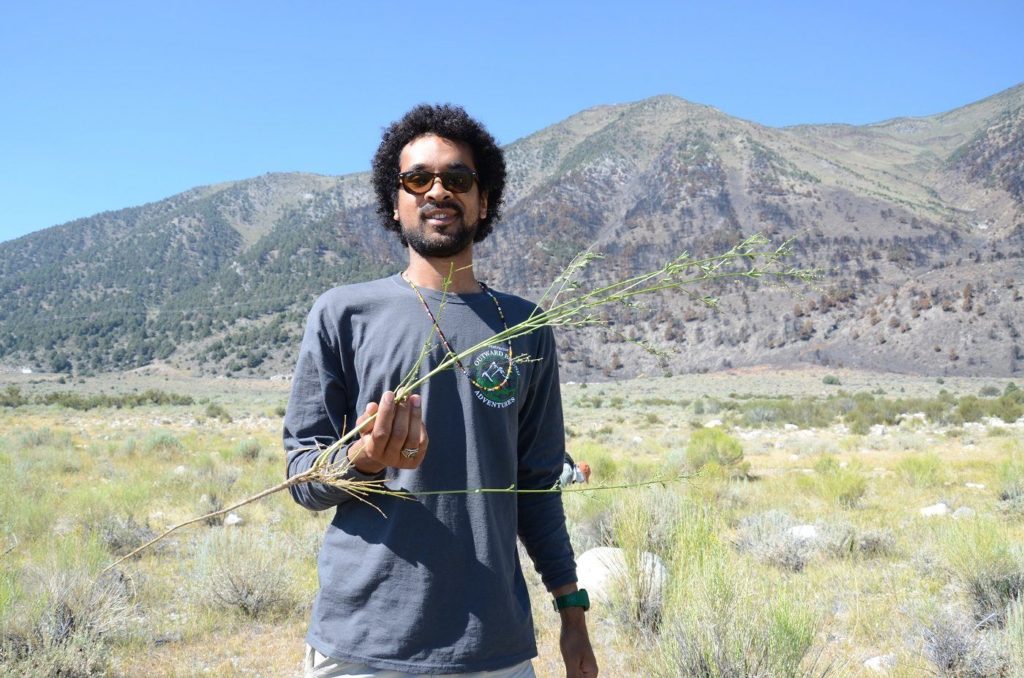

That’s why Ward was at Mono Lake last week with a group of high school kids from Compton and Pasadena. As a certified lead instructor with Outward Bound Adventures, he teaches kids in the Los Angeles area about nature and environmental issues. Importantly for his project, the trips also give him a chance to listen.

“You can’t be a leader without ingratiating yourself with the community,” Ward says. “I want to see what the needs and demands are, and then mold my project around that.”

But first things first—he had to take away their cell phones. It was an unpopular move, but necessary to make sure the teenagers fully connected with nature and each other. On the road to Mono Lake, Ward and his team made several educational stops to keep the kids engaged. They visited the otherworldly Vasquez Rocks, where Ward described how the unique geological formations were used in movies such as The Flintstones and Planet of the Apes (2001). They also stopped by a fish hatchery and a solar plant, where they discussed alternative energy sources.

At their Sierra Nevada destination, they toured the lake talking about water supply and the impact of the drought. Migratory birds use the lake as a pit stop, so what would happen to them if it wasn’t there? The kids watched brine shrimp mating in cups. They also learned practical skills for camping and hiking. And they bonded with hands-on activities—cooking food together, removing invasive clover and swimming.

By the end of the trip, the students forgot to ask for their phones back. Instead, they watched a sky painted deep pinks, oranges and maroon by a sunset—through the haze of a nearby wildfire. “The kids have never seen anything like this, even just being under the stars and seeing constellations,” Ward says.

Ward hopes they’ll take what they learned home to fight for better conditions in their neighborhoods. “If you’re never able to leave your community, you’re unable to envision something different,” he says. But the excursion was also about opening up new career paths. Due to lack of funding, Ward says, many urban schools lack strong science programs that would allow kids to see a future in environmental fields.

It’s a reality he knows too well. Ward grew up in East Palo Alto in a community he calls “wild.” He spent much of his childhood indoors, avoiding the street life, reading National Geographic magazines and dreaming of travel. Families in his neighborhood would enter a lottery to go to better schools in neighboring Palo Alto. Ward was one of the lucky ones who got in, but quickly found himself ostracized on both sides—by the community he wasn’t from and by the one he left behind. He focused his attention on his studies, especially history.

Ward says the idea that the Black community hasn’t been part of the environmental conversation is a misnomer. Organizations like MOVE fought against toxic environments in Philadelphia, and more recently, the community of Flint, Michigan rallied against lead in their water. But part of the misconception is based in historical reality, he says. As the country industrialized from the 1940s to the 1960s, Black people were still busy fighting for basic civil rights like voting.

“Toxic waste was really concentrated in Black communities,” Ward says. “You have to be enfranchised to even begin to say ‘we don’t want this in our backyard.’ ”

The community Ward grew up in looks very different today — gentrified by the tech industry boom, many residents have been displaced. His original intention was to return home to fight for justice, but instead he’s looking to help similar neighborhoods in L.A.

Once Ward understands their environmental needs—this is his first year in L.A.—he plans to unite people from across the region for a summit to inform and empower them. It will be the culmination of his leadership project for UCLA.

“There’s this idea that environmental degradation affects everyone, so we don’t have to figure out how race and class play into that,” Ward says. “Those affected the most are poor and oppressed people. And it’s sad that we don’t get the attention.”