Environmental lobbying’s clean little secret

The public perception is that lobbyists fight for lax regulations, saving businesses money by allowing more pollution—often at great cost to public health and natural resources. That’s only one side…

Corporate lobbyists get a bad rap when it comes to environmental issues, but it may not be completely deserved.

The public perception is that lobbyists fight for lax regulations, saving businesses money by allowing more pollution—often at great cost to public health and natural resources.

That’s only one side of the story. Green firms lobby, too. And they’re spending nearly as much as the biggest polluters, according to a recent study from UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

The study, which will be published in the June edition of Academy of Management Discoveries, is the first to explore the relationship between lobbying and environmental performance, said lead author Magali Delmas.

“People have this picture of lobbyists being these horrible people who are hampering social progress,” Delmas said. “That’s not always the case.”

Researchers examined the lobbying activities of 1,000 firms from a variety of business sectors, from energy to financial services. They assessed the firms’ environmental performance based on the amount of greenhouse gases each emitted.

As one might expect, dirty firms such as Chevron and Exxon Mobil spent huge sums to lobby the government. In 2008 alone, Exxon spent $29 million while emitting 306 million tons of greenhouse gases. But clean firms were also big spenders. Pacific Gas & Electric—a utility company in eco-conscious northern California—spent $27 million that same year, despite emitting just 4.26 million tons of greenhouse gases.

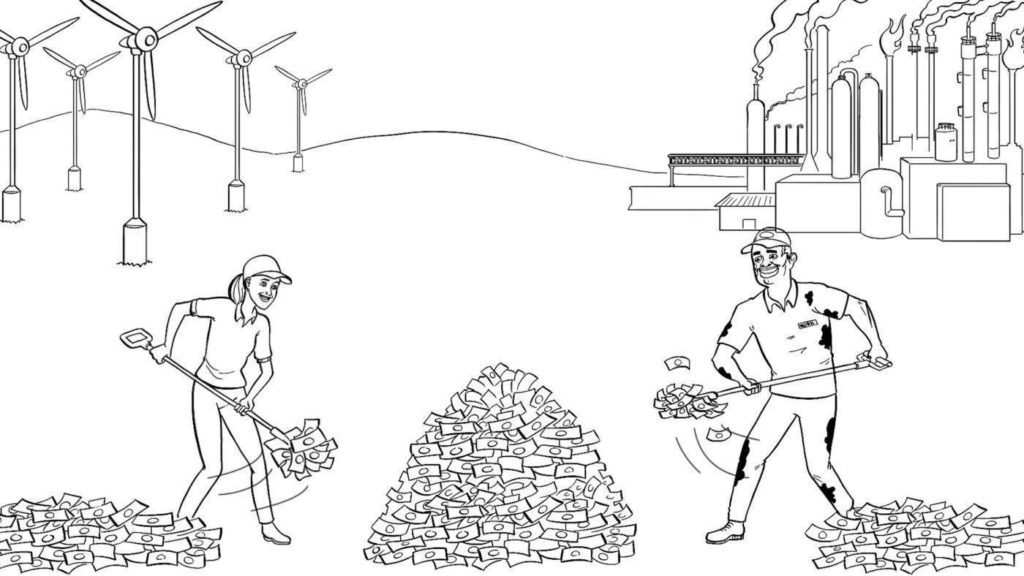

Clean and dirty firms were equally likely to contract heavy-hitting external lobbyists, experts that are brought in for high stakes policy battles. The study also found that firms with middle-of-the road environmental performance didn’t spend as much, having less to gain from changes in laws and regulations. (For more on the research, watch this whiteboard animation.)

While there is no way to be sure what the exact motives behind the lobbying activities were, it is assumed that green firms lobby for more stringent regulations, which give them a competitive advantage.

The paper’s findings were based on a four year period, but they represent a longer trend in corporate lobbying, said Randy Haynie, president of the National Association of State Lobbyists.

“Society has changed over the last two decades,” Haynie said. “There’s no doubt that large national corporations now understand the importance of environmental issues.”

In general, lobbying activities have risen dramatically since Haynie joined the profession in 1980. “Everybody woke up and learned that if they’re not at the table, they’re not going to get fed,” he said.

However, not everyone has the same access to that table. Nonprofit organizations often struggle to compete with the deep pockets of private business.

“We see more and more environmentally friendly organizations in play,” Haynie said. “They just don’t have the resources to fight when an industry lines up on one side.”

Published: