Our environmental future under the Trump administration

These pleas for support stress the urgency of donating now—immediately—before the great ship of Mother Earth sinks. The money they request, of course, is intended to build a war chest…

If you have ever given money to an environmental nonprofit, you’ve likely been flooded with e-mails over the past few months.

These pleas for support stress the urgency of donating now—immediately—before the great ship of Mother Earth sinks. The money they request, of course, is intended to build a war chest to battle what many believe will be President-elect Donald Trump’s assault on the environment. The requests inevitably make full use of the scariest possible quotes one can find in the public record. Passion is great, but analysis is better. If we learned anything from 2016, it is that there has been too much rancor and name-calling.

Let’s take a look at the incoming Trump administration.

How bad is it by the numbers?

Below is a table of the latest names associated with major Trump appointments and well-documented public positions that could be viewed as anti-environment.

|

Appointment |

Name |

Support Clean Power Plan? |

Climate Science Denier? |

|

Secretary of Commerce |

Wilbur Ross |

||

|

Attorney General |

Jeff Sessions |

||

|

Secretary of Energy |

Rick Perry |

No |

|

|

Secretary of Labor |

Andrew Puzder |

No information found |

No information found |

|

Secretary of Defense |

James Mattis |

Yes |

No |

|

Secretary of Housing and Urban Development |

Ben Carson |

||

|

Secretary of State |

Rex W. Tillerson |

No |

|

|

Secretary of Transportation |

Elaine Chao |

No |

No information found |

|

Secretary of Health and Human Services |

Tom Price |

No |

Yes |

|

Secretary of Education |

Betsy DeVos |

||

|

Secretary of the Interior |

Ryan Zinke |

No |

|

|

Secretary of the Treasury |

Steven Mnuchin |

||

|

Vice President |

Mike Pence |

||

|

Secretary of Homeland Security |

John F. Kelly |

||

|

Administrator of the Small Business Administration |

Linda McMahon |

No information found |

No information found |

|

Director of the Office of Management and Budget |

Mick Mulvaney |

||

|

Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency |

Scott Pruitt |

||

|

Ambassador of United States to the United Nations |

Nikki Haley |

No public declaration |

|

|

White House Chief of Staff |

Reince Priebus |

No information found |

All but Mike Pence and Reince Priebus require Senate confirmation. Seven of the 19 nominees are on record as climate change deniers—or they at least don’t think things are as bad as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and climate scientists assert. Only one of them favors President Obama’s Clean Power Plan.

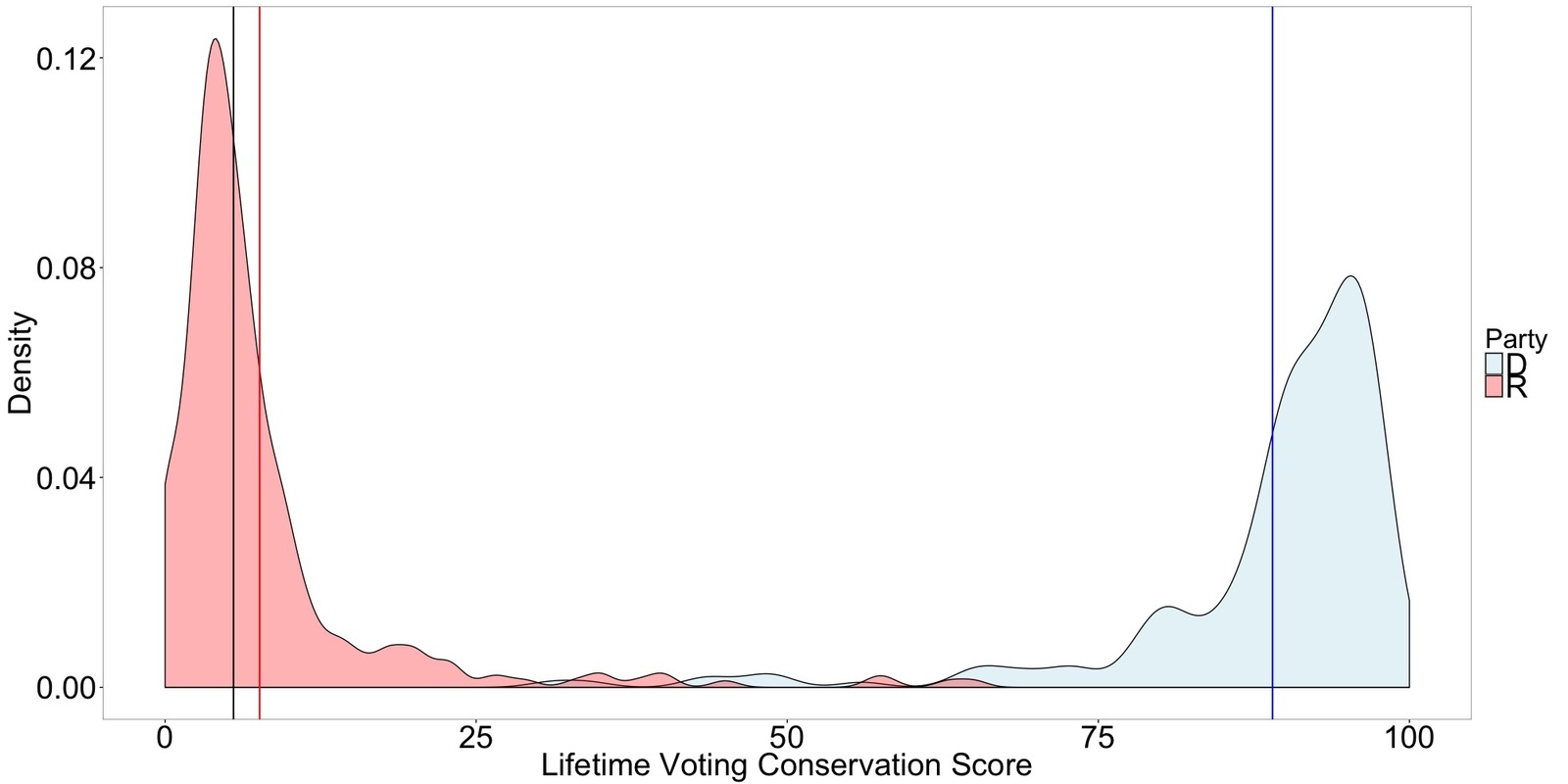

Four nominees have previously served in Congress, so they have a voting record to look at. The League of Conservation Voters tracks each member of Congress’s lifetime voting record on environmental topics, assigning scores. Low scores equate with anti-environmental votes. The lifetime scores of Mulvaney, Price, Sessions and Zinke are 7, 5, 7 and 3, respectively—that’s out of a possible 100. These scores are at the very low end, even for Republicans. (see Figure 1 below.)

Figure 1. Probability density plots of lifetime voting environmental scores for the 114th (2015-2016) congress. The probability must be between zero and 1, and the area under each curve sums to a 100 percent probability (or a 1 on the scale above). Both independents in the Senate (data not shown) have a lifetime score of 95. Members of Congress with party affiliations entail 98 senators (54 Republicans: 44 Democrats) and 435 representatives (248 Republicans: 187 Democrats). Note that the average lifetime score for Trumps nominees (mean = 5.5), indicated with a black line on the graph, is lower than the average Republican score (mean for Republicans = 7.6 (red line), Democrats = 89 (blue line)).

The stated positions of several nominees cannot be dismissed lightly. These are not off-the-cuff remarks, but represent consistent and repeatedly stated policy positions. For example, Scott Pruitt, who has been put forth to lead the EPA, is one of several state attorneys general suing the EPA over the Clean Power Plan, and has relentlessly accused the EPA of overreaching its authority and being a “wayward federal agency.” Rick Perry, Trump’s selection for Energy Secretary, disputes that climate change is happening or that it is caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

But it is not fair to say that Trump’s selections are unanimously anti-environment. As a general with the Marine Corps, James Mattis (proposed for Secretary of Defense) was strident about weaning the armed services off of traditional energy. Along with other military leaders, Mattis identified climate change as one of the biggest security threats facing the U.S. (See Joint Operating Environment, 2010). And Ryan Zinke—selected for Secretary of Interior—could in some sense be called a conservationist, despite favoring energy development on federal lands. Zinke was the only Republican to vote for an amendment that would have permanently authorized the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Like many conservationists, he is an avid hunter and fisherman. He voted against the GOP’s 2016 budget because it called for selling public lands, and he resigned as a delegate to the Republican Convention last summer because the party platform called for selling off public land.

Remarkably, the fact that roughly one-third of Trump appointees are climate deniers is an improvement over the views of the American public. Over half of Americans either do not believe climate change is real or think it is due to natural causes. So in terms of climate denial, at least, Trump’s cabinet is more environmental than the U.S. public.

Much of what’s being depicted as anti-environment is actually anti-regulation. The idea that there are too many rules and that federal government encroaches on states’ rights is a major part of Trump’s populism. That does not make it less worrisome, but it may help to realize that we’re largely not dealing with people who wake up in the morning and seek to ravage the environment. We empathize with frustrations about regulations—which only grow in number and complexity while never seeming to be streamlined or removed (Augustine’s Laws, 1997).

This leaves a few openings. Rick Perry, who denies climate change, was a big promoter of wind energy in Texas—making Texas the nation’s leading wind power producer. He even partnered with Democrats to invest $7 billion in transmission lines and infrastructure to connect wind power to the grid. Meanwhile, Rex Tillerson, CEO of Exxon and Trump’s pick for Secretary of State, testified before Congress in 2010 that “there is no question the climate is changing, that one of the contributors to climate change are greenhouse gases that are a result of industrial activities.” He supports a carbon tax as well as investments in carbon capture, sequestration and biofuels.

Trump’s cabinet does not represent the first time an incoming president made appointments that terrified the environmental community. In 1981, James Watt became Secretary of the Interior under Ronald Reagan, promising to open wilderness areas to mining and drilling, weaken the Endangered Species Act, eliminate strip-mining controls, and offer all of America’s offshore oil (a billion acres) up for immediate leasing. He failed on all accounts. Of course, Congress was Democratically controlled then. Trump does not have that obstacle.

If he wants to, how easy will it be for Trump to reverse existing climate, energy and environmental regulations?

Trump has already backed off from his pledge to abolish the EPA to save money—probably after realizing he lacked the authority to do so. He certainly can hobble enforcement or issue a stifling executive order that insists on a cost-benefit analysis for regulations. He can review and rescind Obama’s most recent regulations. But first there must be public notice and a comment process. After that, there’s litigation. It would add up to years of struggle.

For sure, Trump can scuttle U.S. leadership on the Paris climate accord. But the energy transformation is already underway, and there are too many members of his own leadership and too many Republicans in Congress who support clean energy. The Clean Power Plan is at risk, but much of what it was intended to accomplish is happening due to market conditions, state regulations and federal tax incentives that are locked in.

In short, there is almost no way that Obama’s environmental legacy can be totally unraveled. It can be rolled back, but the process would be 10 steps forward and then three or four steps back. Simply put, the federal government has serious limits to its powers. As long as environmentalists emphasize human well-being and the economic benefits of a healthy environment there will be no large-scale public rejection of environmental values.

Like all of our colleagues, we are dismayed at possible setbacks and what may or may not be an anti-science and anti-data mood gaining traction. But our worry is less about the loss of regulations and more about a dumbing down of environmental discussions, with science and data relegated to the sidelines.

As usual, advocacy and political action will remain important courses of action. But scientists and teachers also bear responsibility. Too often, the environmental community relies on fear, and the data are overwhelming that that strategy simply does not work. Dire messaging can be counter-productive (PDF), as can moral arguments based on “care and hope,” which resonate with liberals but not conservatives. Lastly, a remarkable study of students in Los Angeles and Minneapolis, as well as online surveys of university students revealed an across-the-board failure—from middle school to high school and college—to impart the skills necessary to evaluate the credibility of online or social media information. To quote from the study (PDF):

“Overall, young people’s ability to reason about information on the Internet can be summed up in one word: bleak.”

That is particularly concerning with the current uptick in fake-news. Discernment and critical thinking are key.

Now is the time for public engagement, and a time to lay a better foundation for public discourse about climate change and the environment. Universities must lead the way.