Colorado River delta fish risk extinction through interbreeding due to lack of freshwater

UCLA study is a warning for other river systems around the world

At the start of the 20th century, the Colorado River flowed free from the Rocky Mountains to northern Mexico, where it supported a unique delta habitat. But that changed over the past 80 years as the population of the Southwest U.S. swelled: Today, the river supplies water to 40 million people and 4 million acres of crops along its route.

Now, the river does not really reach the Sea of Cortez in Mexico. What remains in the river Delta is salty tidewater.

New UCLA research shows that the changes have had a dramatic effect on a species of silverside fish, Colpichthys hubbsi, that lives only in the delta. The silverside now commonly breed with the False grunion, a more widespread species that thrives in saltier waters.

As a result, there are growing numbers of hybrid fish in the habitat, and fewer true silverside fish — which is bad news for the species’ survival.

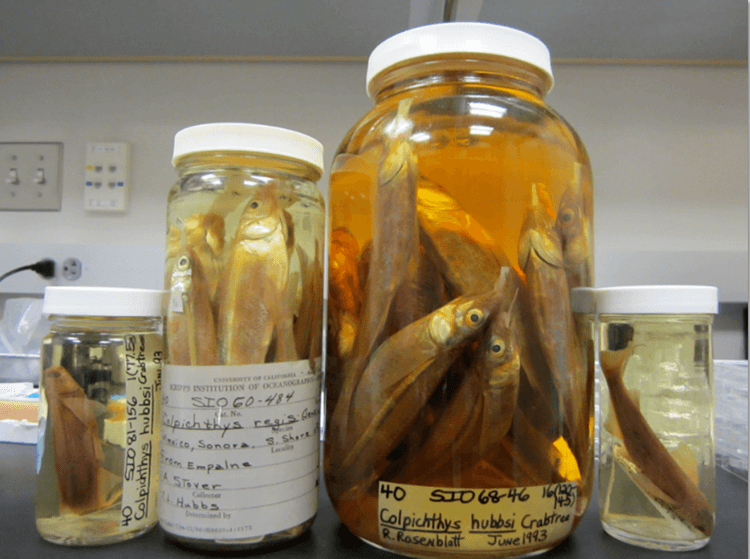

To understand how interbreeding is affecting the silverside, David Jacobs, a UCLA professor of ecology and evolutionary biology in the UCLA College, and Clive Long Fung Lau, a UCLA doctoral student, examined samples of the fish from the 1960s and 1970s that had been preserved by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

They found that the physical signs of interbreeding — such as differences in the gas bladders that help fish maintain buoyancy — that are evident in silverside living in the delta today were not present in the older specimens.

“Hybridization creates a real risk of extinction, as the very identity of the fish may be eliminated,” said Jacobs, one of the paper’s authors and a member of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. “In this case, the hybrids are all in the delta silverside range, so the interbreeding may be in the process of eliminating delta species whose habitat has dramatically changed. And other groups of fishes and crabs appear to have evolved as ecological species restricted to the Colorado Delta these also appear to be at risk.”

Beyond the loss of freshwater for farming and drinking water along the river’s route, the delta habitat is also being hurt by the fact that so much sediment is being trapped by dams upstream. More sediment used to flow downstream, where it formed an important part of the silverside’s habitat.

“Our efforts should be united toward finding ways to have more fresh water in the delta, and this could be done through organized water management throughout the West,” Jacobs said.

But, he added, those regions already have significantly reduced their use of water from the river, and seemingly much larger reductions would be needed to affect the salinity of the lower delta.

“Any substantial further reductions inherently create conflicts, as our everyday food consumption is dependent on this upstream freshwater, and so is the sustainability of our economy,” he said.

The dwindling populations of the silverside fish and other species also highlights broader global issues caused by humans’ still-growing use of water from major rivers.

“We have taken all the water we can from the Colorado, but water extraction continues to accelerate in large river systems around the world,” Jacobs said. “Thus, the loss of ecological species in deltas and estuaries around the world is also likely accelerating. The effects on wildlife are especially pronounced at deltas, located at the end of the line after everyone upstream has taken what they need for farming, hydroelectric power and residential use.”

Jacobs said more studies are needed to understand the risks of how water extraction affects wildlife in river deltas worldwide — both directly through habitat change and indirectly through interbreeding of formerly separate ecological species, as appears to be the case in the UCLA study.

TOP IMAGE: The Colorado River Delta. | Photo by Stuart Rankin via Flickr.