Has climate change made wildfire terrorism a serious threat?

The whole hillside, dotted with red California fuchsia, was clearly ready to burn. Anyone could walk up one of the many roads and trails in these parched hills and strike…

Hiking a ridge in the Santa Monica Mountains, I could make out the Santa Monica Pier, the crescent of beach along the bay and the skyline of downtown Los Angeles. “Fantastic view,” I thought, with a simultaneous thought: “It would take just one bad actor.”

The whole hillside, dotted with red California fuchsia, was clearly ready to burn. Anyone could walk up one of the many roads and trails in these parched hills and strike a match.

Wildfire-friendly conditions are expected to increase with climate change, and yet wildfire terrorism is seldom discussed. Perhaps that’s due to fear of giving malicious people ideas. But I can’t be the only one to wonder: How much of a threat is it? Is there a real risk? And if so, how is it being dealt with?

Earlier this week, President Donald Trump removed climate change from a list of national security threats—saying regulations are the real threat. At the same time, “unprecedented” wildfires were raging in Southern California, late-season fires that UCLA climate experts say are consistent with what is expected as our regional climate changes.

Terrorism by wildfire, or pyroterrorism, is relatively lightly studied. Many references lead back to the master’s thesis of a Marine Corps major, Robert Baird, titled “Pyro-terrorism: The Threat of Arson Induced Forest Fires as a Future Terrorism Weapon of Mass Destruction.” In it, Baird assesses the prospects of terrorists unleashing “latent energy in the nation’s forests to achieve the effect of a weapon of mass destruction.”

Pyroterrorism is different from arson. It has a political and psychological effect, the thesis explains. The textbook definition of terrorism is a violent act with four characteristics: it is politically motivated, perpetrated by an organization, targets non-combatants, and has a psychological impact.

Our fear of pyroterrorism—effectively to the point of verbal paralysis—is understandable. And it’s not new.

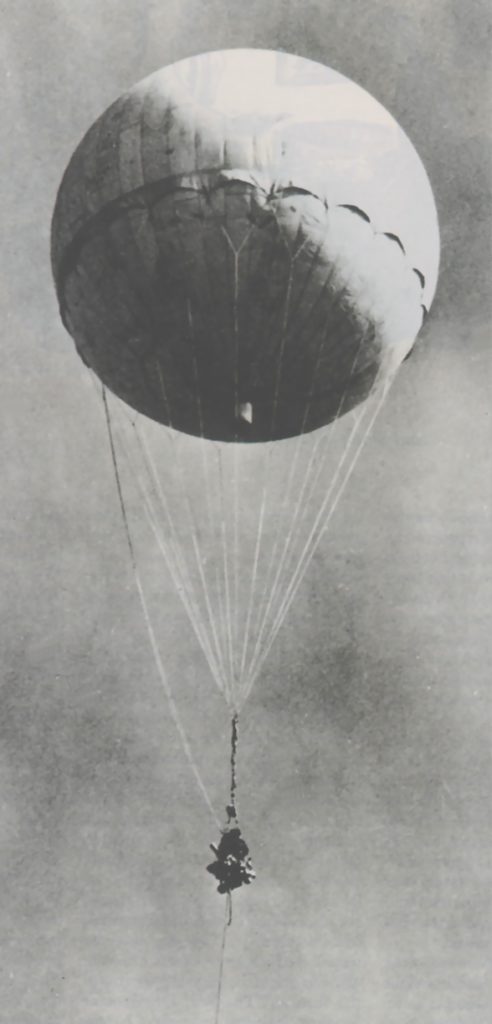

In theory, multiple fires could be planned and executed to create a disaster equal to a multi-megaton nuclear weapon—delivering similar results with much less effort and risk. Baird’s thesis recalls the panic caused by fire-balloons during World War II. Japan launched 9,000 hydrogen balloons with timed explosive devices, intended to ride the jet stream across the Pacific Ocean. Only about 300 reached the United States mainland, but they had an outsized psychological effect, causing a diversion of resources.

Things could have been worse. Baird notes “if the fire-balloon attack had occurred during the summer fire season in California, and especially during the Santa Ana winds, the result would have been a significantly greater level of physical destruction.”

As the Thomas Fire continues to rage in Southern California, at least one top official has considered the threat of modern pyroterrorism—Baird himself. After serving in a number of leadership positions at fire agencies, in April he was named director of the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region. He is currently on duty battling the wildfire, which is expected to become the largest recorded in state history.

Other experts have tried to find out how much of a risk pyroterrorism really is. Mississippi State University’s professors Robert Grala, Jason Gordon, and Hugh Medal sent online surveys to 1,600 experts from a range of fire and security agencies. When asked if wildfires could be used in a terrorism plot, 85 percent of respondents said yes. More than half said they thought wildfires from terrorism would be more damaging than naturally occurring wildfires.

“The issue here is that when you have a naturally occurring wildfire, even if you have a multiple point issue, they are randomly distributed,” Grala said. Strategically placing the points where the fire comes from would affect how it spreads over the landscape.

At the same time, the experts thought the likelihood of a wildfire terrorism attack wasn’t very high, even though it was possible. Why not? One reason could simply be that it hasn’t happened. There are incidents of “eco-terrorism,” or domestic groups using fire to make a political point—for example, the FBI is still investigating an incident from 14 years ago, when the Earth Liberation Front took responsibility for setting a housing project on fire in San Diego.

There has been some concern about wildfire terrorism in other countries, though it’s not clear how authentic it is. After wildfires devastated Israel and the West Bank in November 2016, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu charged that some of the fires had been “arson terrorism”. Other Israeli and Palestinian officials in the region refuted the claim.

To date, there have been no examples of pyroterrorism by foreign actors against the United States, but that might be dumb luck. There is some evidence terrorists are interested in such a tactic. Some point to a 2012 article in Inspire magazine, Al-Qaeda’s glossy chronicle, which detailed how to construct an “ember bomb” to target forested areas of the U.S as part of its “Open Source Jihad” series, following in the tradition of “Make a bomb in the kitchen of your mom.” (After building and testing the device, California officials found it “highly impractical.”)

One Los Angeles Fire Department official suggested fire might not be as psychologically terrifying as other types of attacks, especially in a region where natural wildfires are a part of life. This also makes sense: wildfires consume brush and rage on the hilly peripheries. Terrorists may prefer to strike the busy heart of a society, where high death tolls are more likely. On the other hand, in an era of climate change, wildfires might induce a new level of fear, as the climate itself is uncanny, an unpredictable actor. Driven by high winds, California’s 2017 fires didn’t just destroy buildings in remote areas—they cut through city blocks in Santa Rosa and Ventura.

Another possible reason pyroterrorism isn’t discussed may be that, while firefighters have an idea of how to address the problem, it could be hard to prevent. Professor Grala noted that while the majority of professionals thought they had adequate training to deal with a terrorist wildfire attack, they were less familiar with how to prevent one or mitigate the risk—though they gave examples of steps that could help, such as increases in personnel, training and equipment. And Baird highlighted the importance of interagency partnerships and information-sharing as part of a cohesive wildland fire strategy.

Ultimately, prevention means dealing with the underlying factors that create the vulnerability: adverse development and climate change. It’s not within the capacity of fire agencies to handle such issues on their own.

The prospect of pyroterrorism raises an important question: Why are we content with living with some forms of vulnerability? We’re willing to spend billions on airport security protocols and other anti-terrorism measures, but when it comes to climate security, we’ve made ourselves totally vulnerable to one crazy person with a match. Pyroterrorism security discourse has been largely driven by the military and not perceived as an issue within our borders. Yet the California drought has “created tinderbox conditions increasing the potential for a terrorist to set severe wildland fires near populated areas and critical infrastructure,” wrote Scott Somers, a professor at Arizona State University with twenty years of fire department experience, in a brief on the vulnerabilities brought by the California drought.

Perhaps we should be identifying and prioritizing critical natural infrastructure, though this would still be a stop-gap measure. Securitizing the landscape or, worse, cordoning it off, would probably be impractical, and would alienate us further from the environment in which we live. The real solution is to deal with the conditions that make pyroterrorism a threat. The underlying causes of climate change make us vulnerable, but the problem goes beyond environmental issues. It includes social concerns, as illustrated by the Skirball Fire, which scorched the hills north of UCLA in Bel Air. That fire was not started by a foreign terrorist. It grew out of an entirely domestic problem: homelessness. It was sparked accidently at an encampment, the L.A. Times reported.

The sheer number and interconnectedness of these social and environmental challenges may seem daunting. But precisely because pyroterrorism touches on so many fields—including climate science, fire dynamics and intelligence analysis—we can bring ample forces to bear on a security concern that will likely become more pressing as our climate continues to change.

TOP IMAGE: A C-130 Hercules aircraft drops flame retardant over Texas in 2011 to help control burning wildfires. | U.S. Air Force photo/Staff Sgt. Daryl McKamey