Climate change could bring much earlier water runoff in Sierra Nevada by century’s end

UCLA climate research shows another way rising temperatures could affect California’s water resources

California has taken a wild weather ride over the past two years: A historic drought finally came to an end, and the winter of 2016–17 was the wettest winter in decades.

Meanwhile, recent studies have projected that climate change will turn up the heat by up to 10 degrees in the Sierra Nevada mountains by the end of the century.

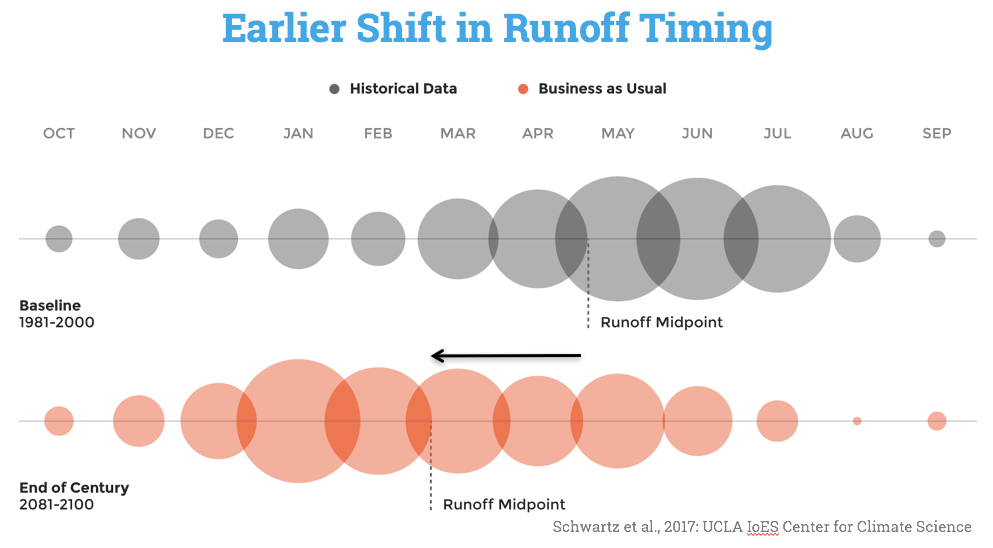

In a study published today in the Journal of Hydrometeorology, UCLA climate scientist Alex Hall and colleagues predicted that by the end of the 21st century, the runoff midpoint for snow and rainwater — the time of year by which half of a year’s precipitation leaves the mountains as runoff — could be an average of 50 days earlier than it is now, and 90 days earlier in some locations. The finding could have serious implications for the state’s water infrastructure, which was not designed to handle such a major shift, according to Hall.

Understanding runoff timing would allow California water managers to better plan for the future.

The changes could be most pronounced at elevations of 6,000 to 8,000 feet above sea level, in part because of high warming rates. Another reason is the albedo effect, a phenomenon in which sunlight and heat are reflected off of white snow, warming the climate and causing snow to melt faster, exposing the darker ground below, which causes additional warming because the bare ground reflects less light and absorbs more heat, melting even more snow to melt.

The Sierra Nevada snowpack provides California with more than half of its fresh water, supporting industry, agriculture and household use. Each spring and summer the melting snow replenishes the state’s water supply when it is most needed. But as the climate continues to warm, more of the precipitation in the Sierra Nevada could fall as rain instead of snow, and the snow that does fall would be expected to melt faster than it has historically.

When precipitation and snowmelt filled reservoirs in early 2017, the rush of water overwhelmed storage capacities. In particular, Northern California’s Oroville Dam suffered severe damage, prompting the evacuation of more than 100,000 people whose homes were downstream.

“We are already in an era where warming is affecting hydrology in California,” Hall said.

The study’s predictions assume that humans will continue emitting greenhouse gases at about the same rate as today. The study found that even if carbon emissions were lower — for example, under the terms of the 2016 Paris climate agreement — runoff would still occur an average of 25 days earlier, and up to 45 days earlier in some places. (However, even that scenario may be in jeopardy if, as has been proposed by the Trump administration, the U.S. pulls out of the accord.)

If runoff dates shift significantly earlier, reservoirs may not be able to maintain sufficient water supply for the state’s needs into the summer. And when reservoirs fill up too quickly, there is a risk of more flooding. The changes could force water managers to find different options for water storage, including groundwater reservoirs.

To predict runoff dates, the researchers used a method called hybrid downscaling, which creates high-resolution simulations from regional climate models. Based on those projections, they used four different carbon emission scenarios from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fifth Assessment Report to compare projections for California’s climate at the end of the 21st century with data on the state’s climate from the end of the 20th.

“How we collect and store groundwater is an important challenge going forward, and one that could help us address the effective loss of storage in the snowpack,” Hall said.

California has already begun to move water supplies underground and modernize dated infrastructure, including through an initiative called WaterFix.

“The project will allow us to dynamically manage the system based on variable weather while improving ecosystem conditions,” said Doug Carlson, a representative for the California Department of Water Resources.

State residents have made changes too: Many installed home water catchment devices, native gardens and gravel lawns during the five-year drought that ended in 2016. And many reduced water consumption and continued to use less water even after the drought was over.

“There is a lot that we can do,” Hall said. “We need to understand where our water comes from and to view it as a precious resource.”

TOP IMAGE: The last of this year’s snowpack melting behind Rock Creek Lake in Inyo National Forest. | Photo by David Colgan.